Step 2_ SESTAO. THE FACTORY CITY

Route 4 km

Route 4 km

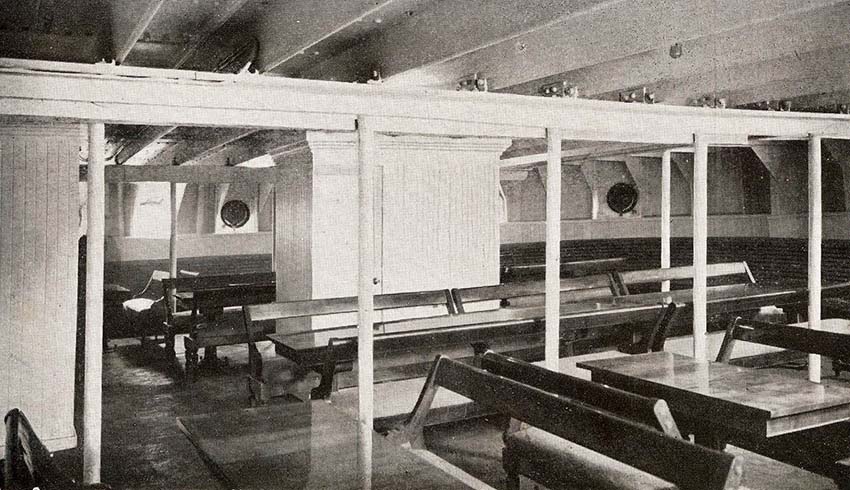

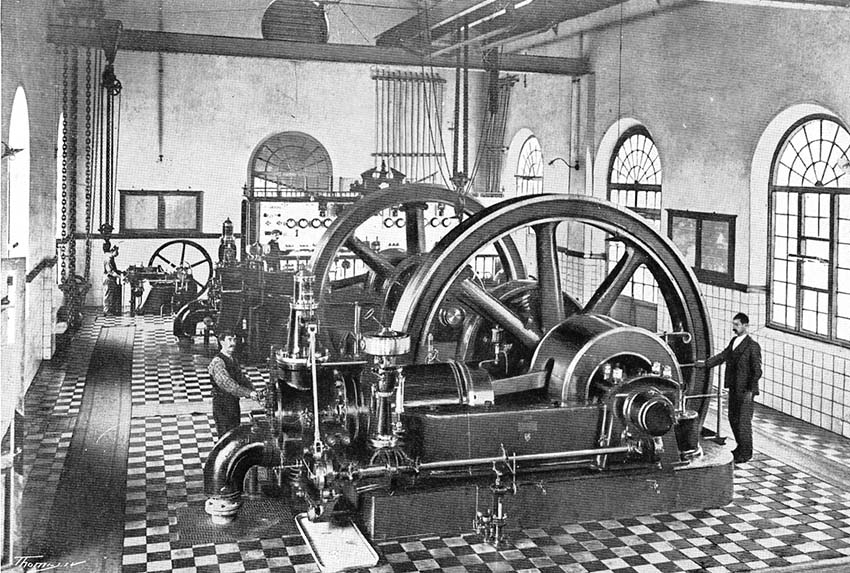

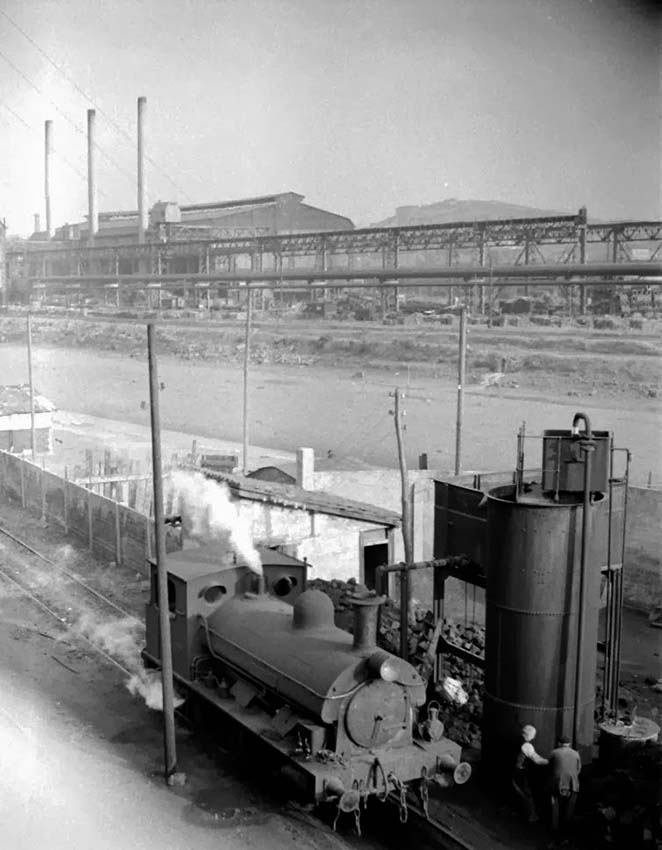

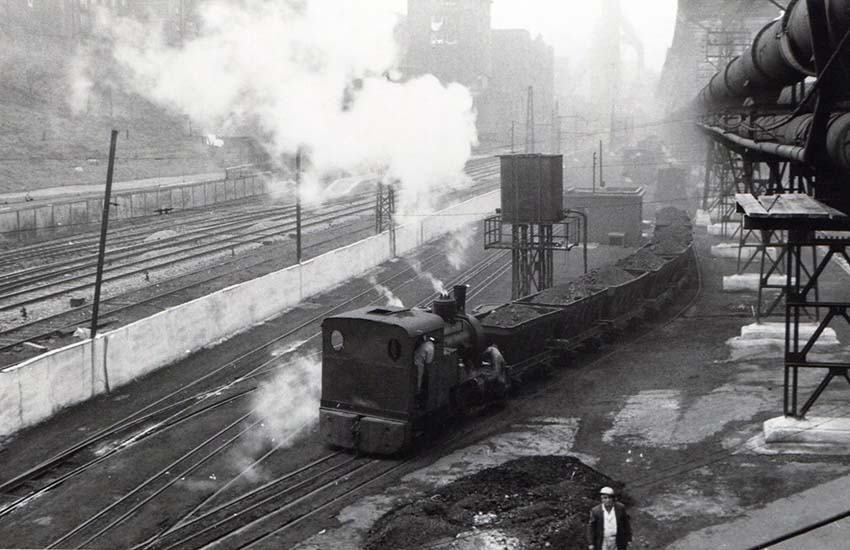

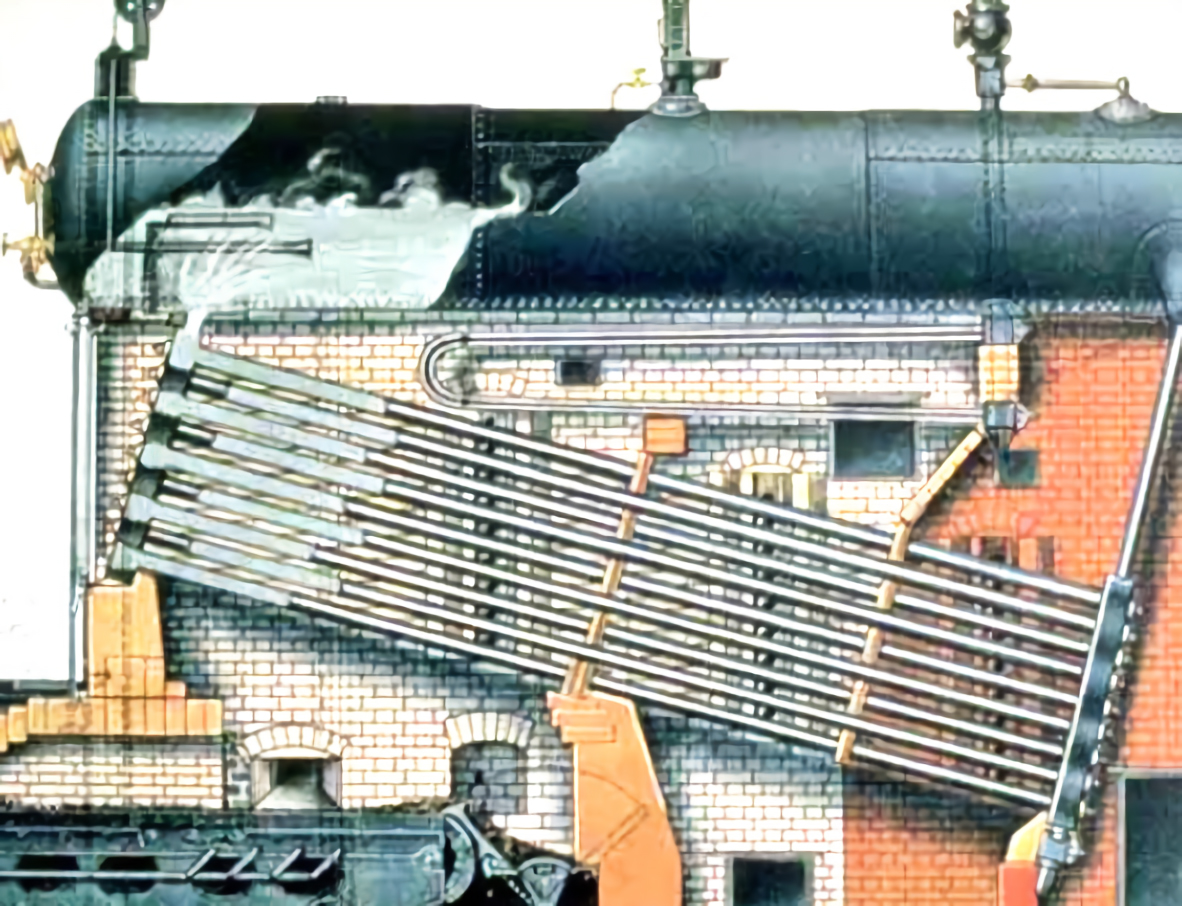

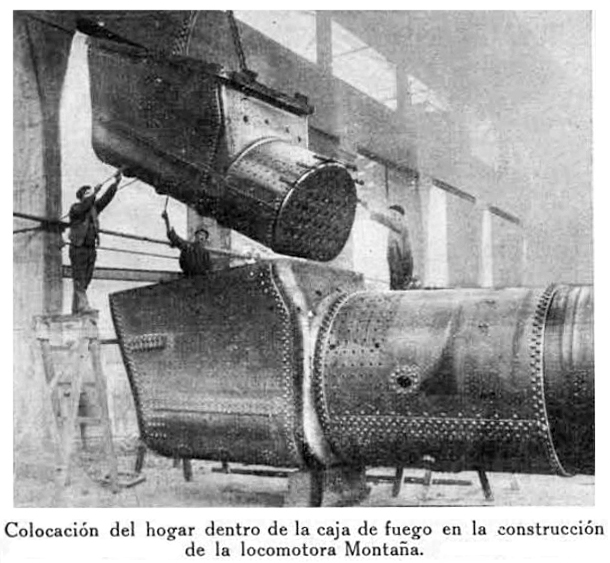

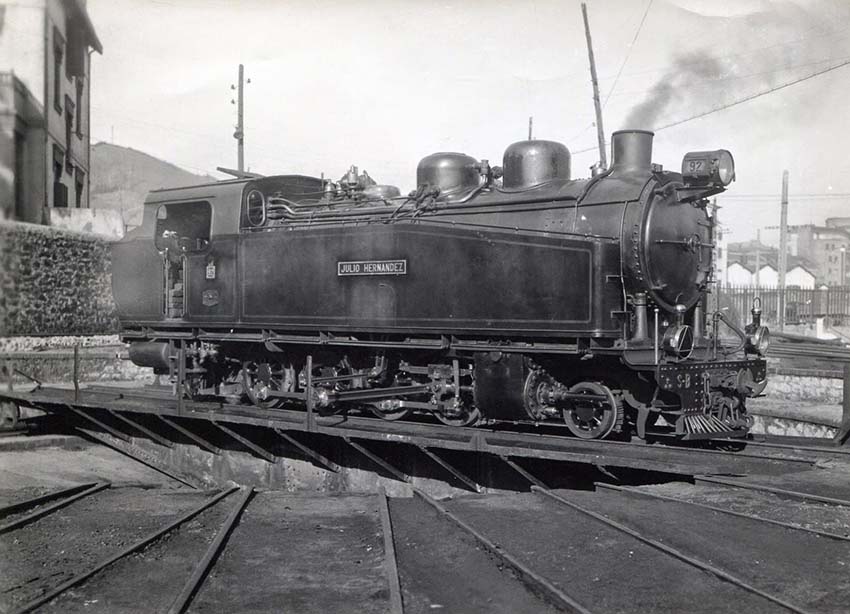

On the other side of the pedestrian bridge you will find one of the many steam engines that were used in AHV (6).

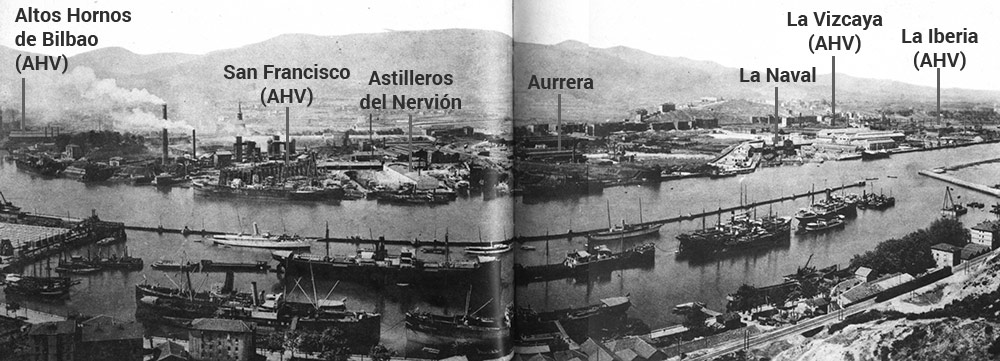

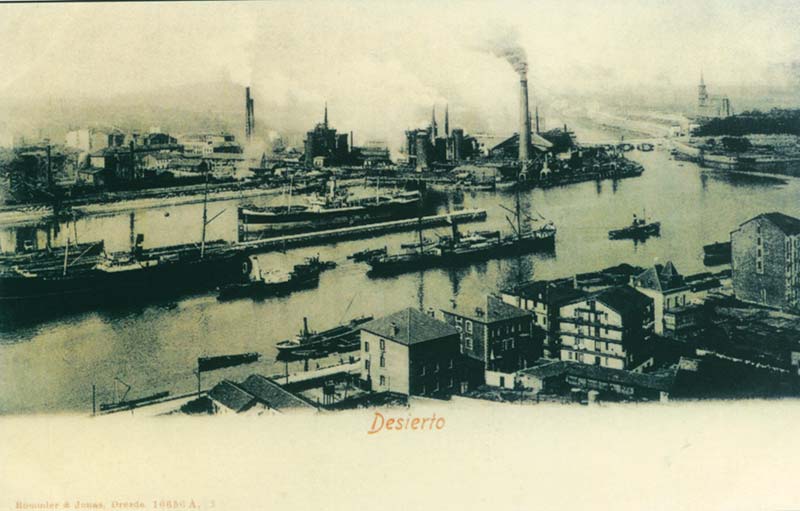

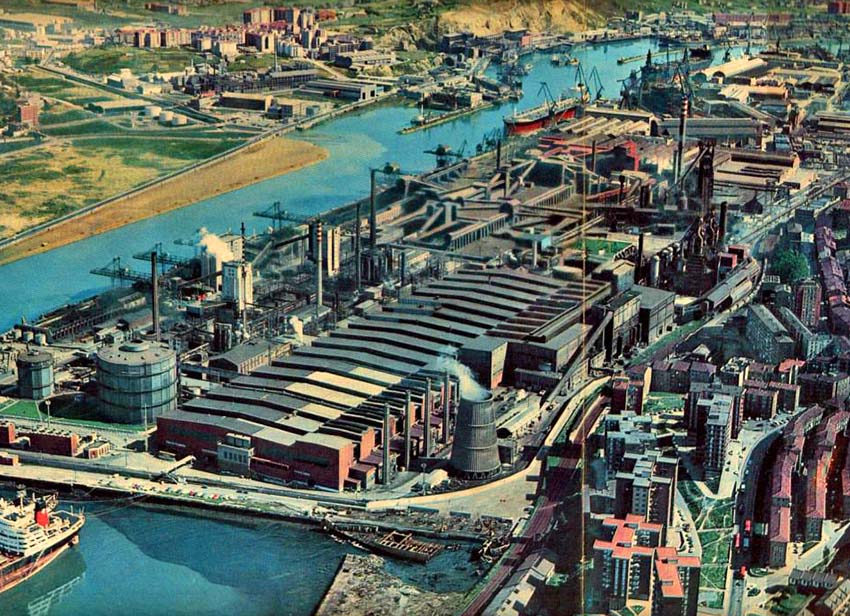

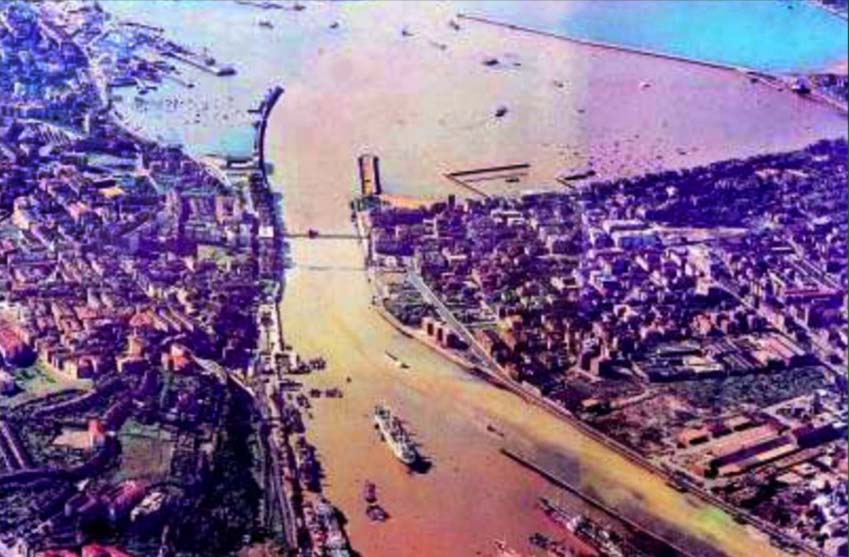

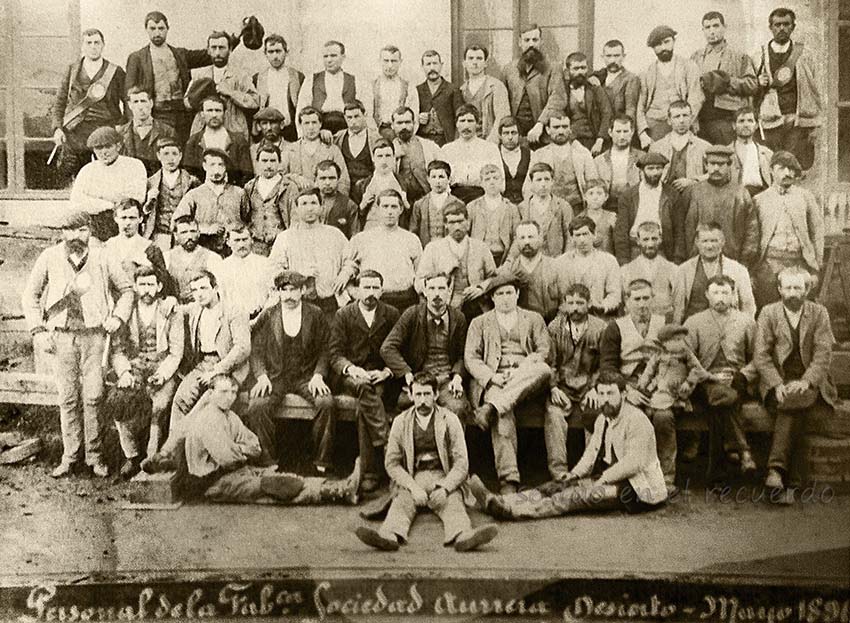

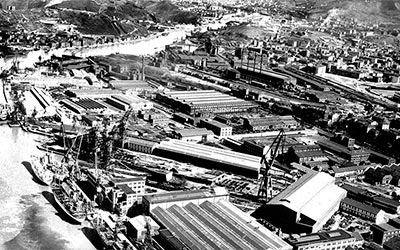

The beginning of "La Punta" area was occupied by two large companies that lay between the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya factory in Barakaldo and the two AHV plants in Sestao: the land abandoned in 1999 by the Aurrera foundry created in 1885, and the area marked by large cranes that can be seen in the grounds of La Naval shipyard.

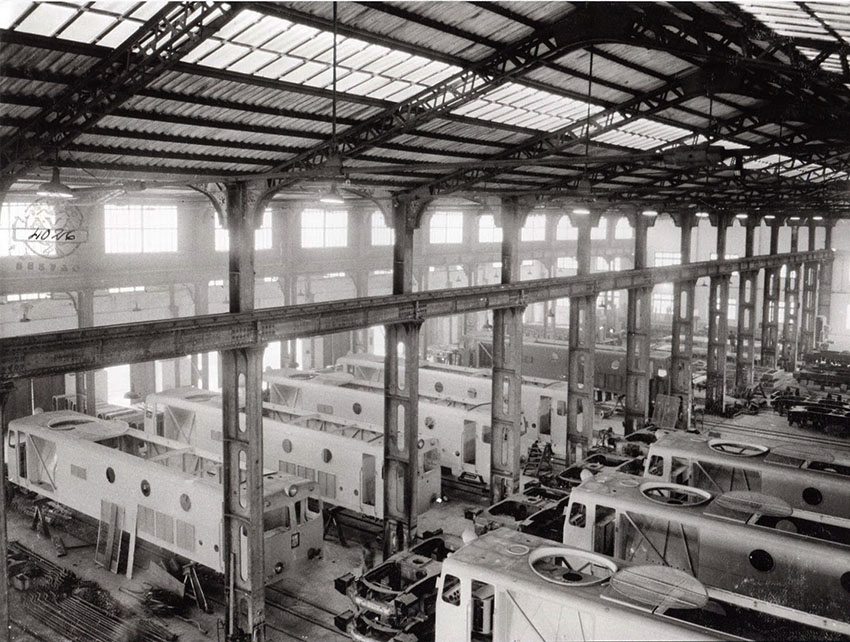

THE LAST GREAT SHIPYARD ON THE RIVER

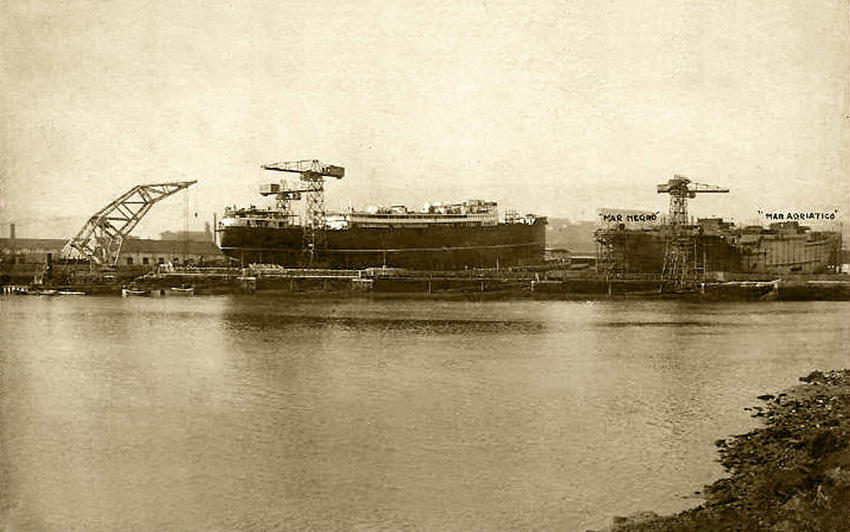

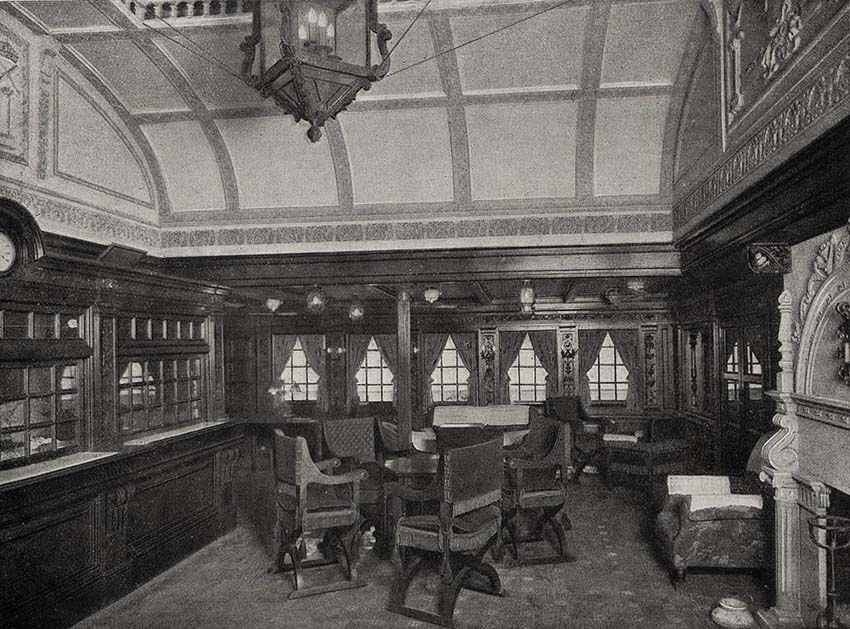

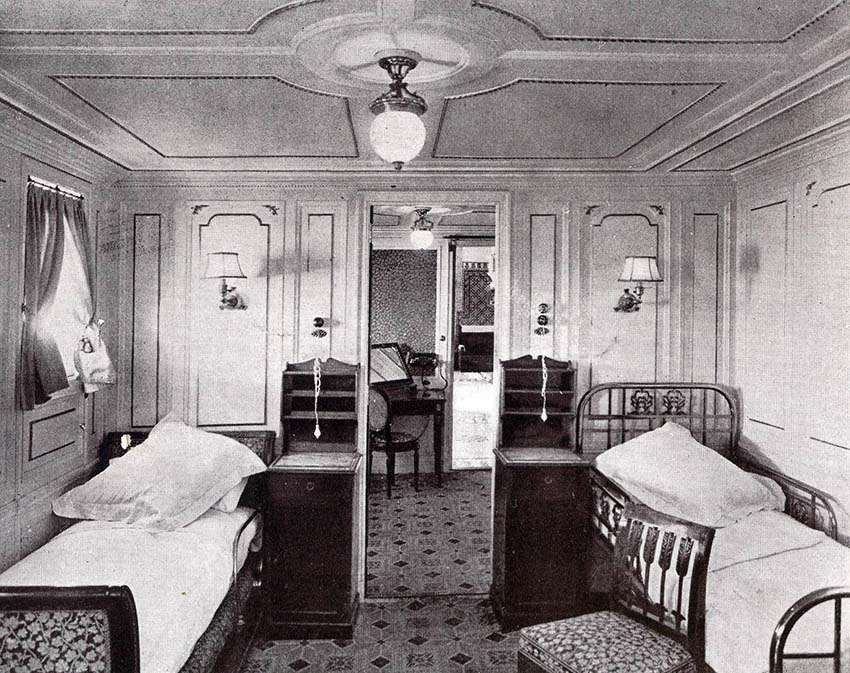

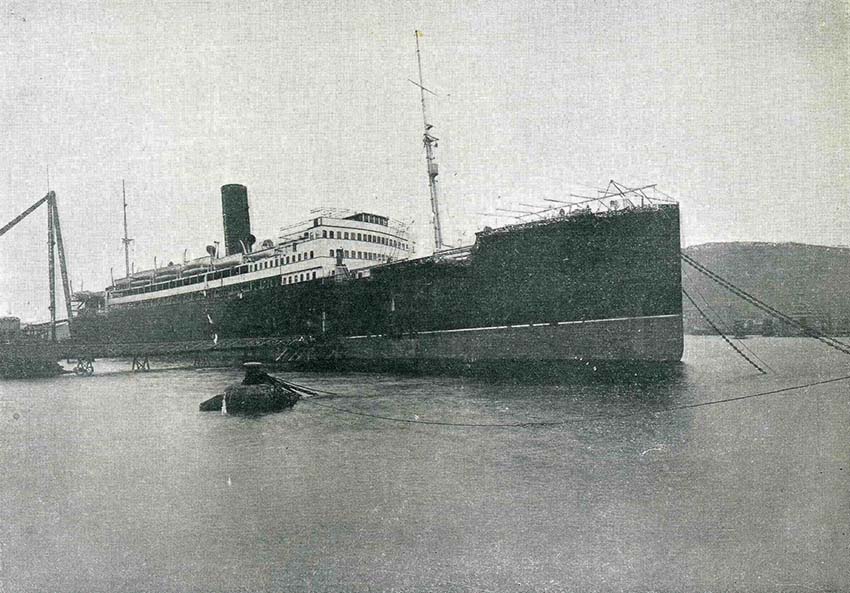

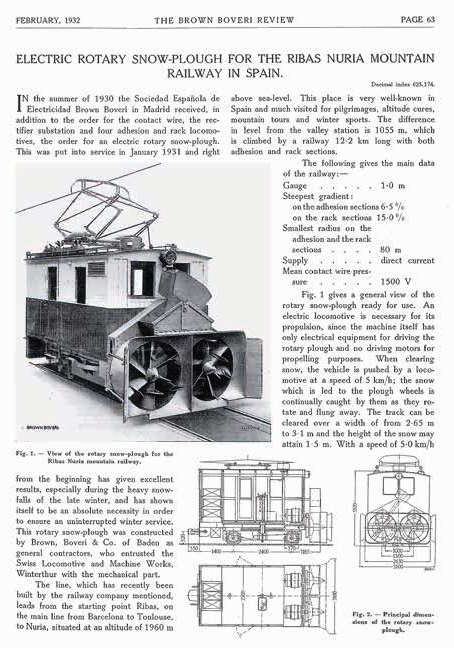

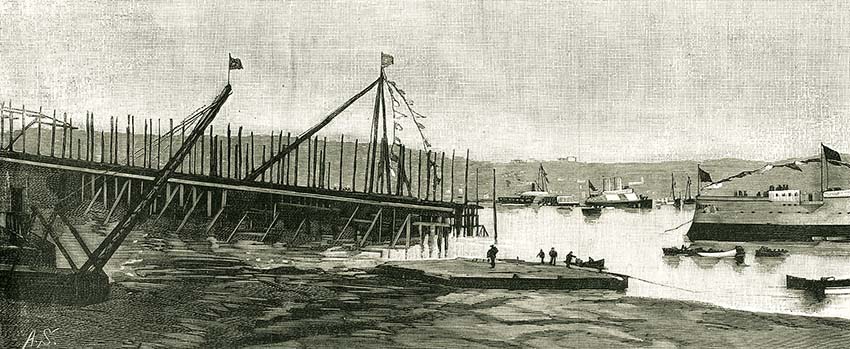

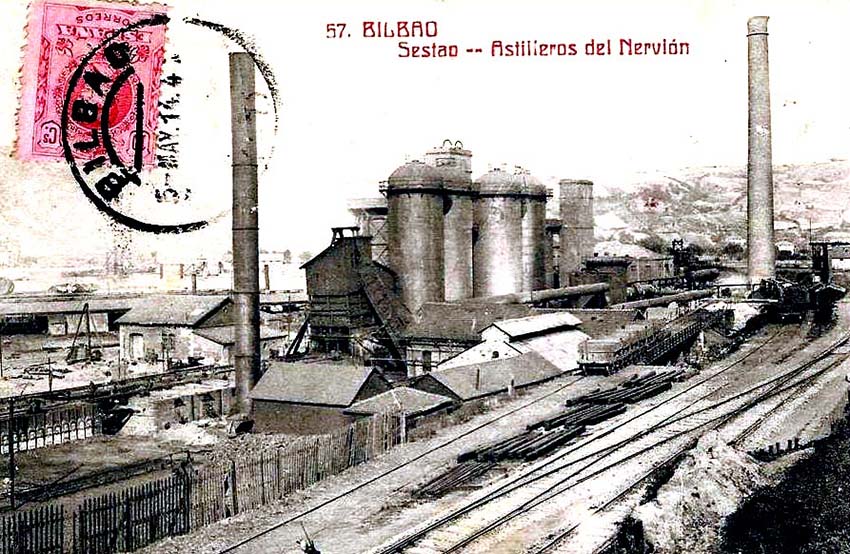

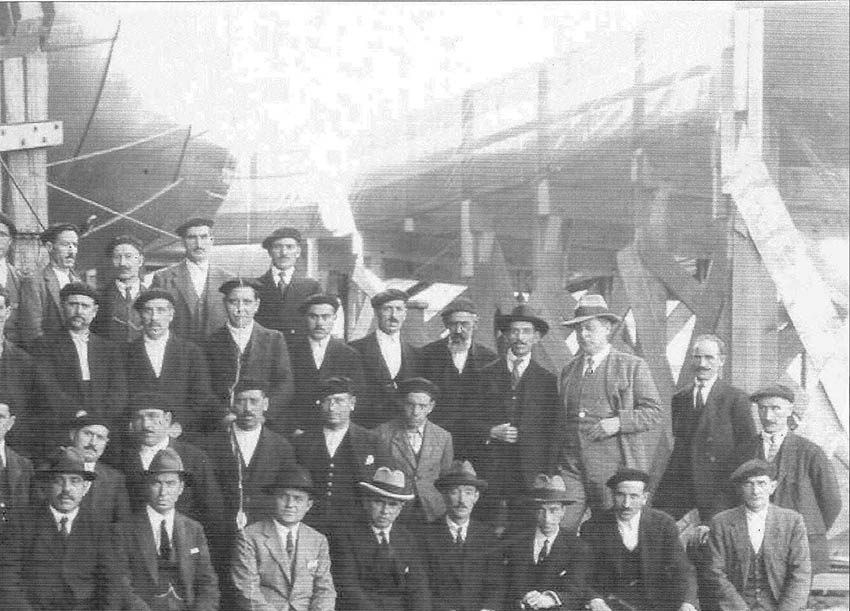

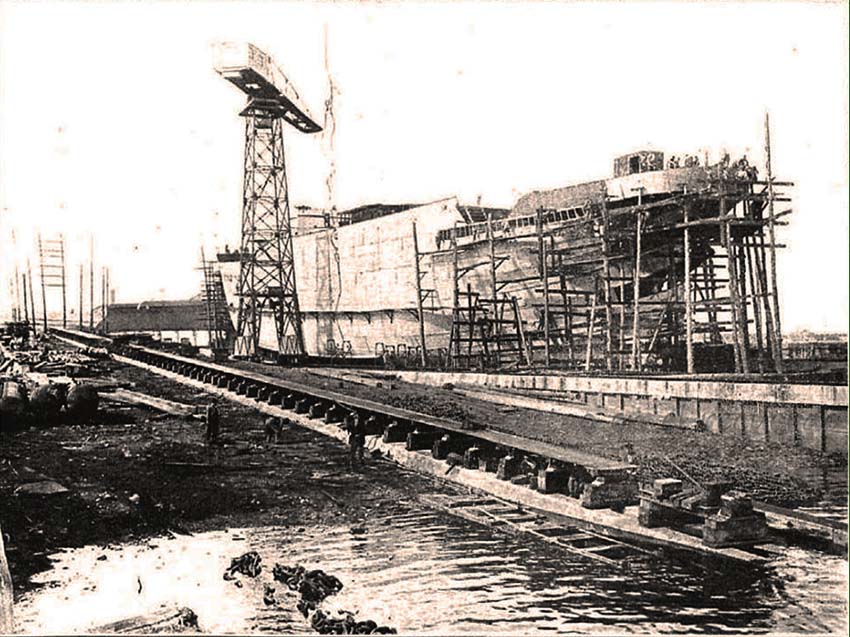

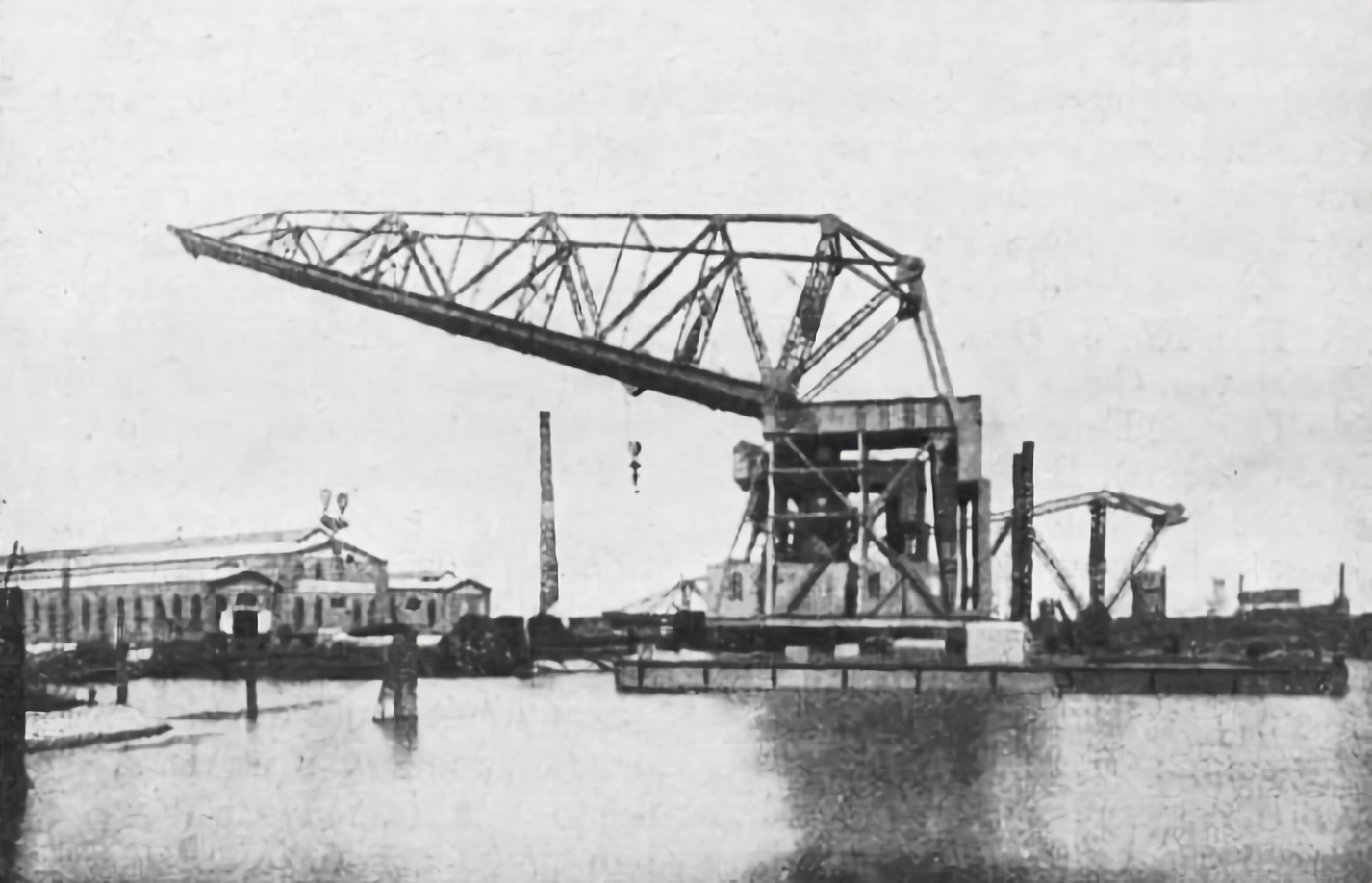

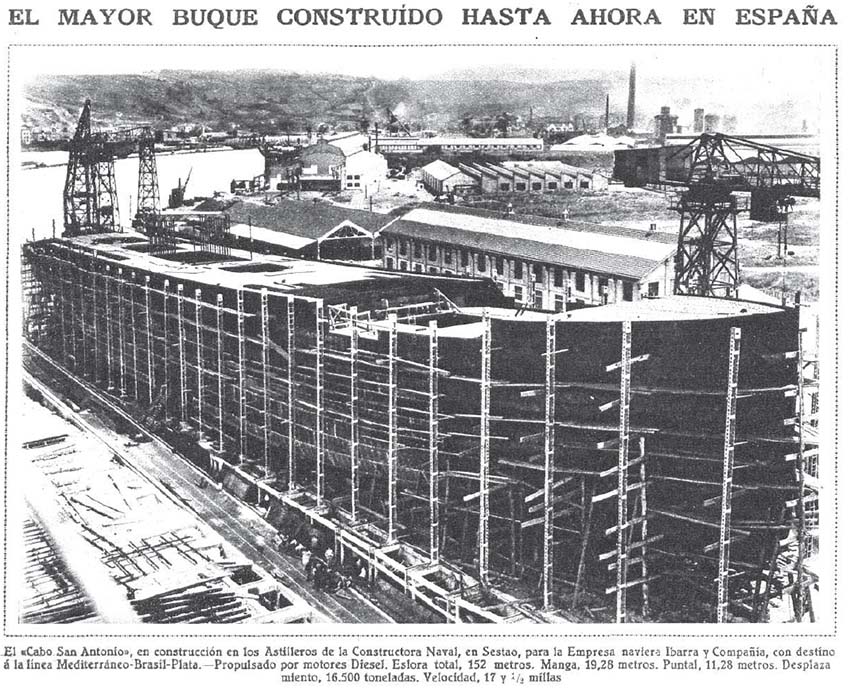

La Naval (7) is the last great shipyard on the river after the closure of the Euskalduna in Bilbao. It began operation in 1916 from the previous company Nervión Shipyards (Astilleros del Nervión), founded in 1888 and pioneers in the construction of steel ships.

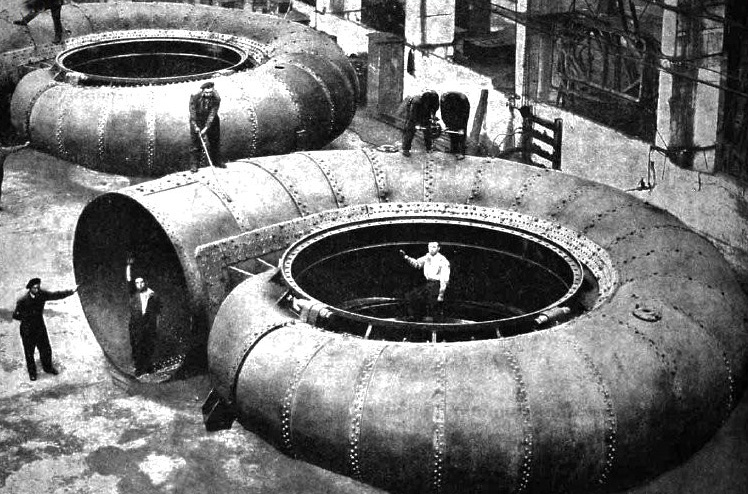

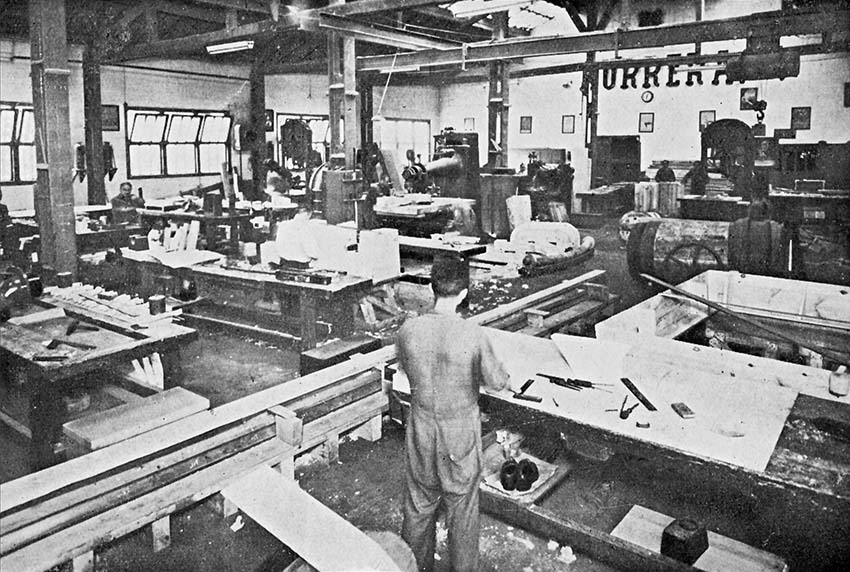

Of its facilities, it is worth noting their building halls, the offices designed by Manuel Mª de Smith and especially dry dock nº 1 which, although substantially modified, belonged to the original shipyard. Its great dimensions measure 26-35m wide, 150m long and 10m deep with the oldest closing caisson in Spain, are the result of the design of facilities aimed to compete for orders for a new naval fleet in the late nineteenth century. As in the case of the shipyard located in Bilbao (Euskalduna), its facilities were also used to produce other articles, including railway rolling stock, cars, cranes...

More pictures

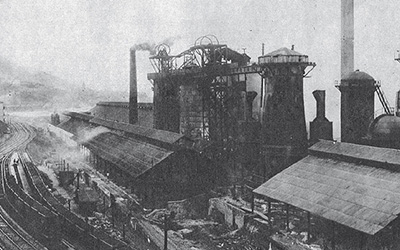

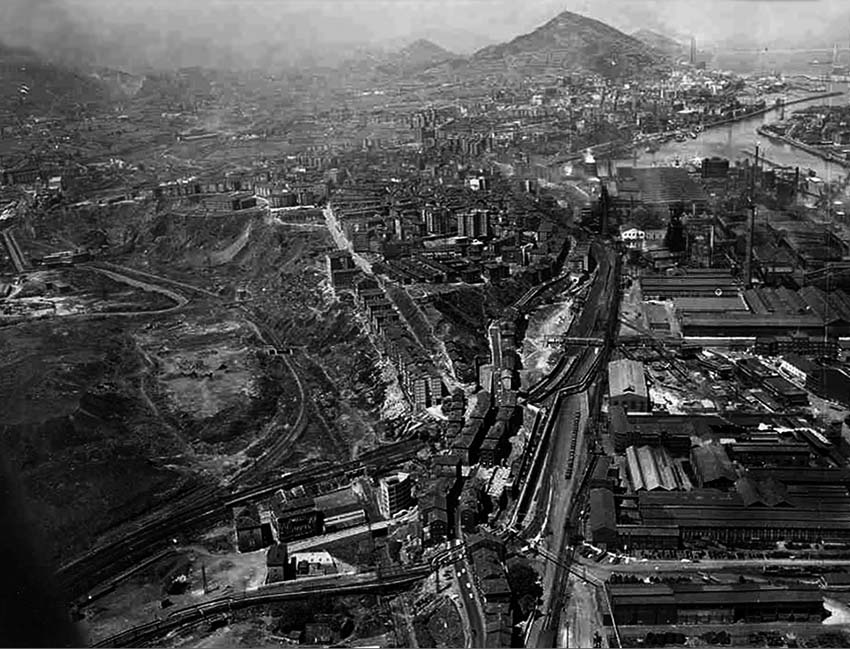

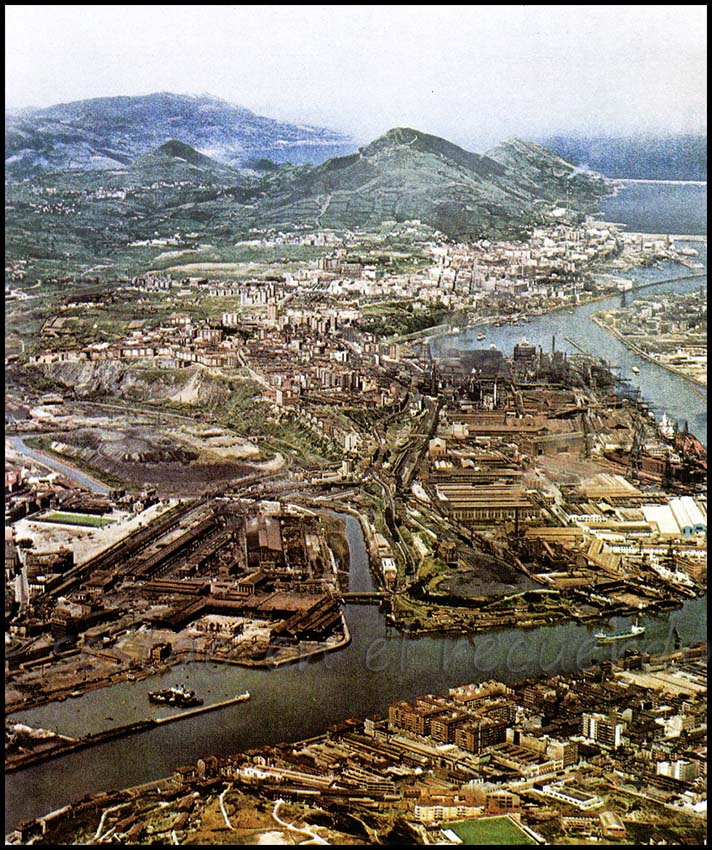

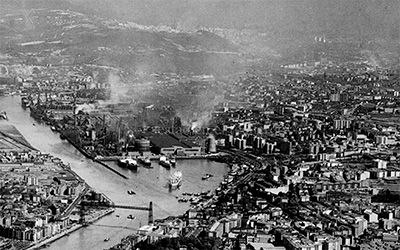

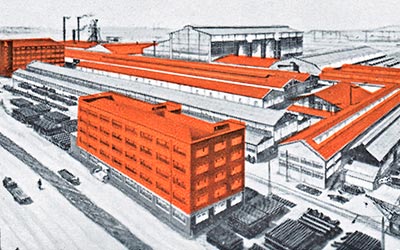

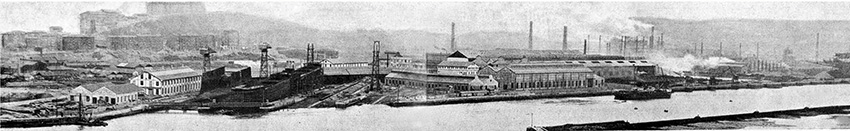

THE INDUSTRIAL FLAGSHIP: ALTOS HORNOS DE VIZCAYA

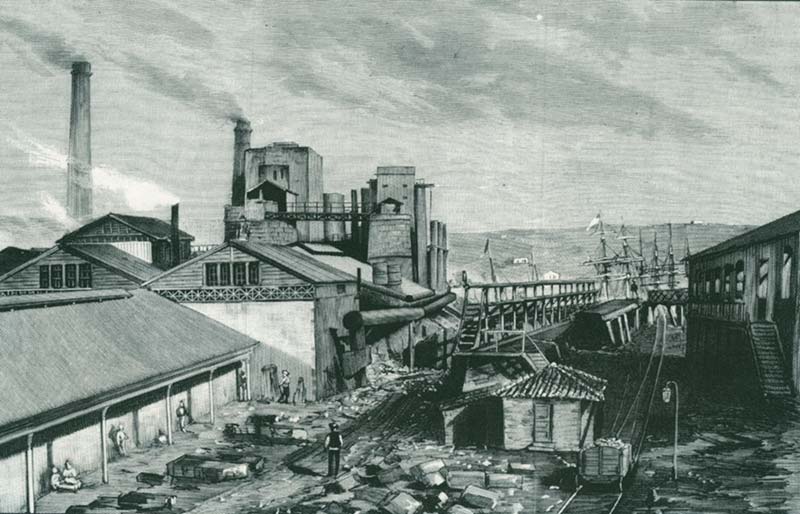

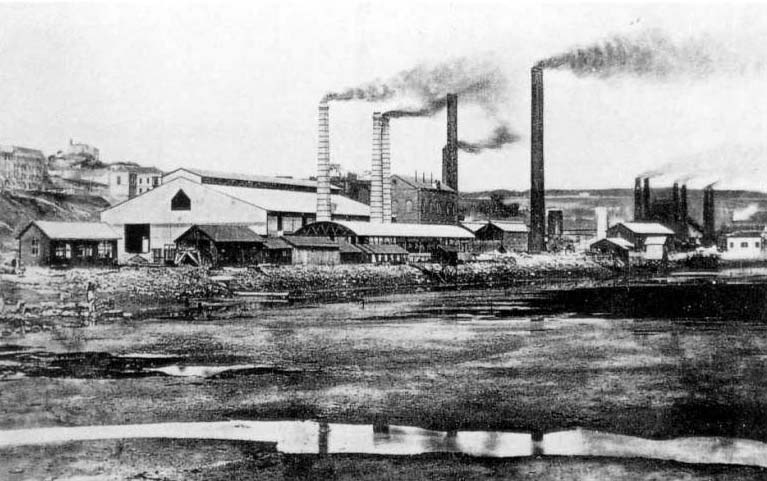

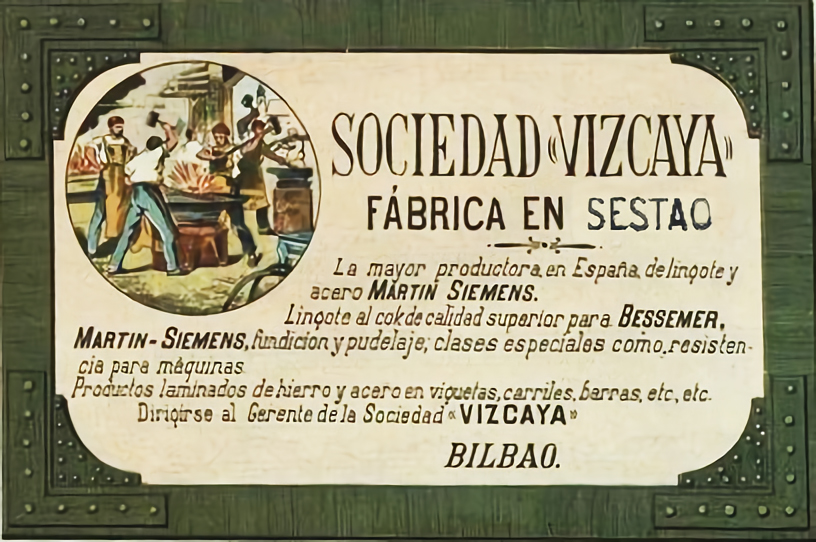

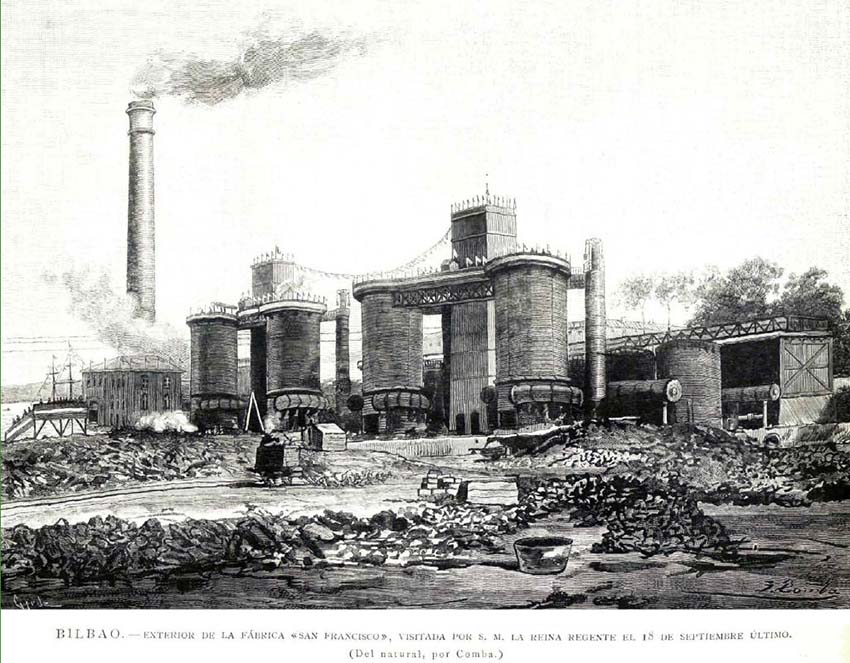

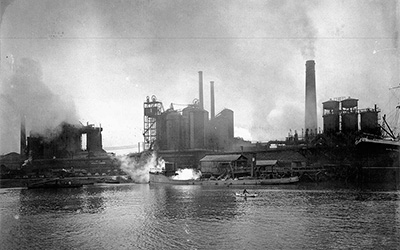

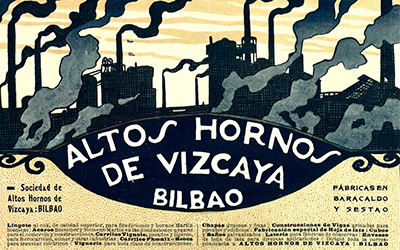

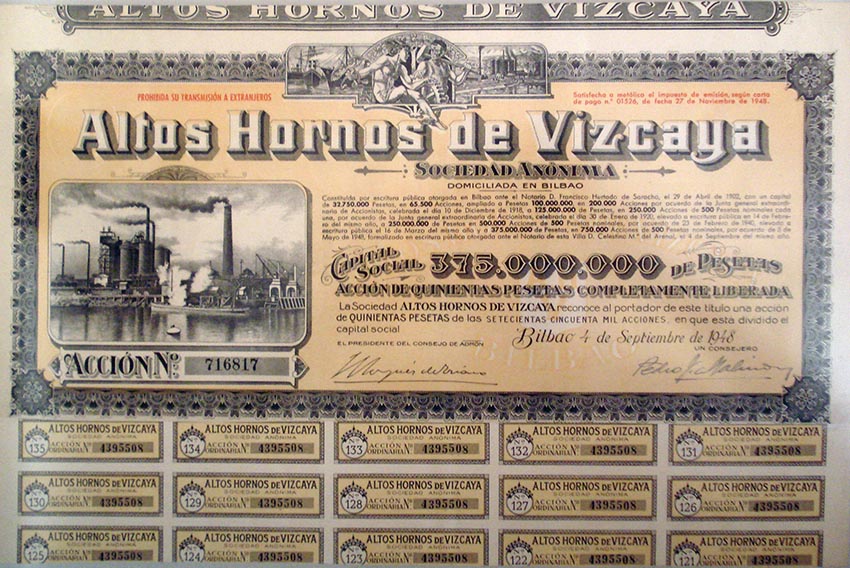

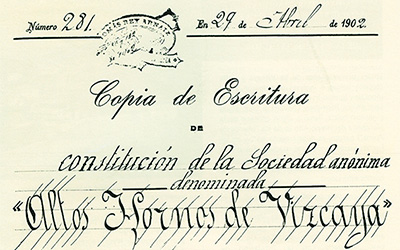

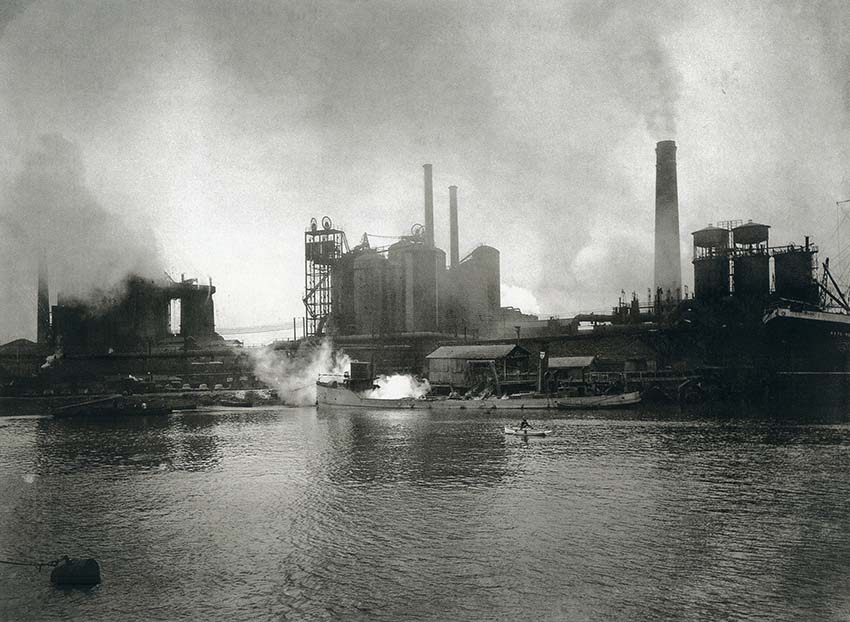

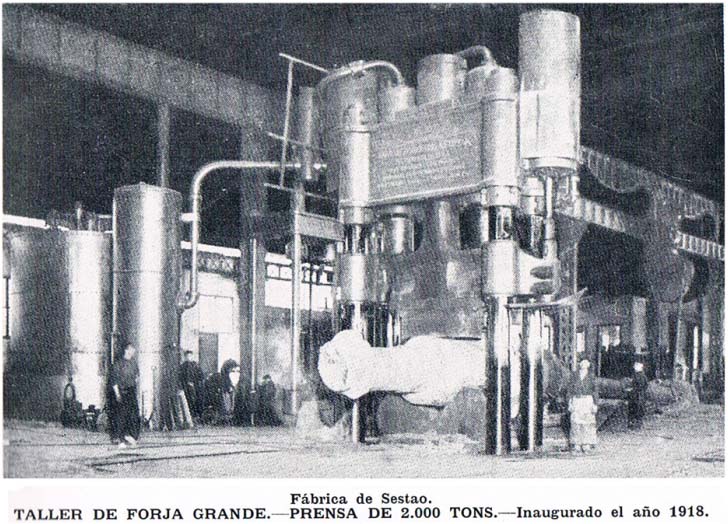

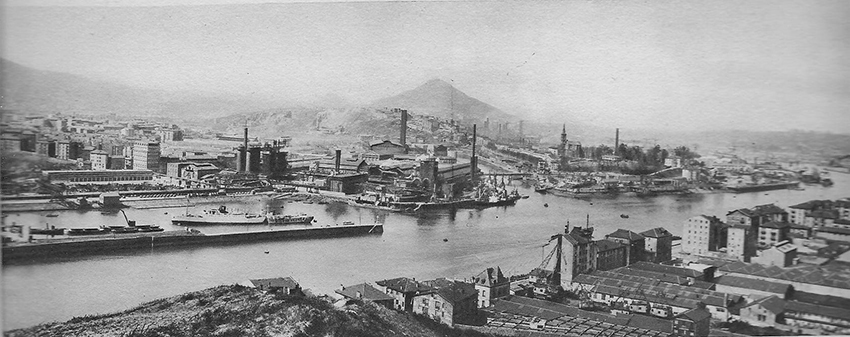

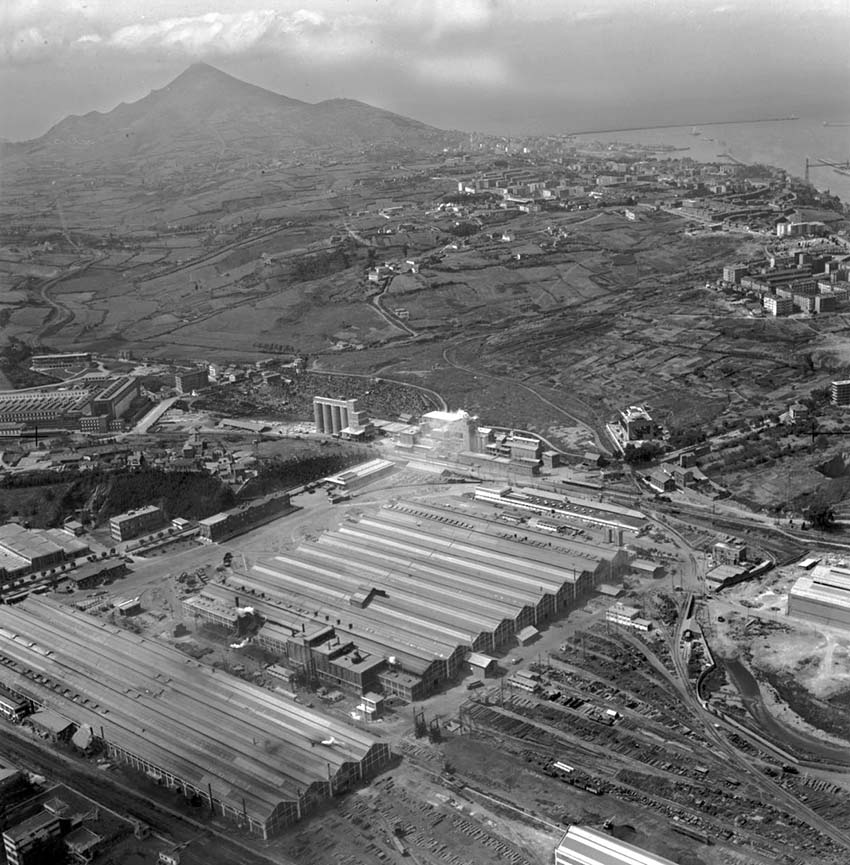

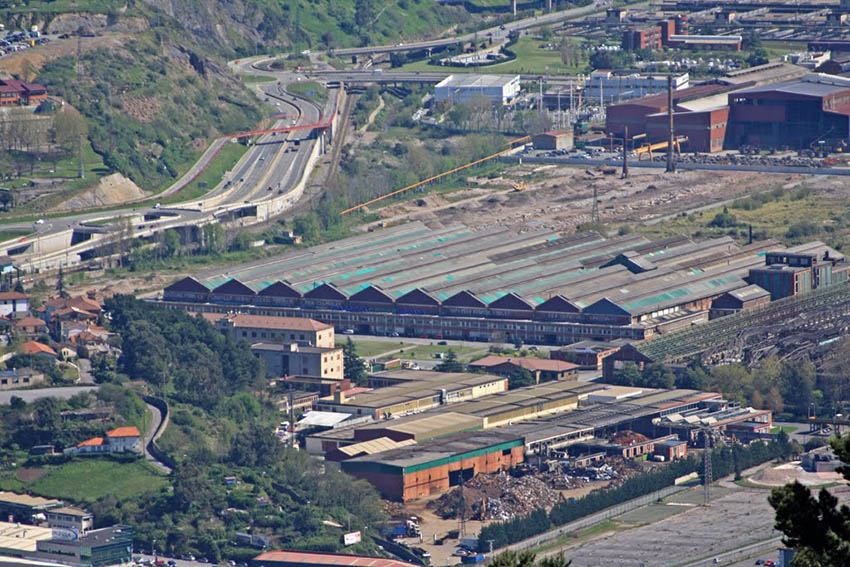

Altos Hornos de Vizcaya was founded in 1902 as a result of the merger of three previous steel companies (Altos Hornos de Bilbao, La Vizcaya and La Iberia) and, after purchasing the factory of San Francisco (1879) it became the most important company in Spain in the first half of the twentieth century. It closed its doors for ever in 1996 and the land in Sestao is now occupied by the ArcelorMittal facilities of the Bizkaia Compact Steelworks.

Altos Hornos was one of the great landowners in Spain, as it owned large mines and became the main shareholder in other steel companies in the country.

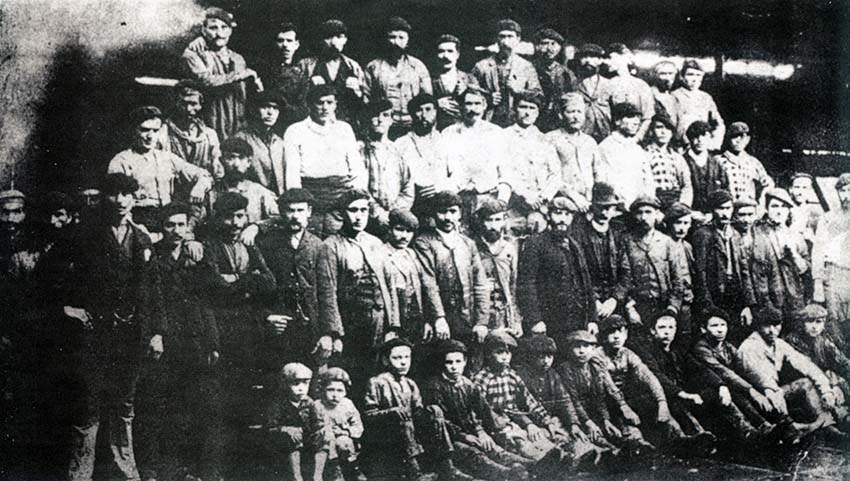

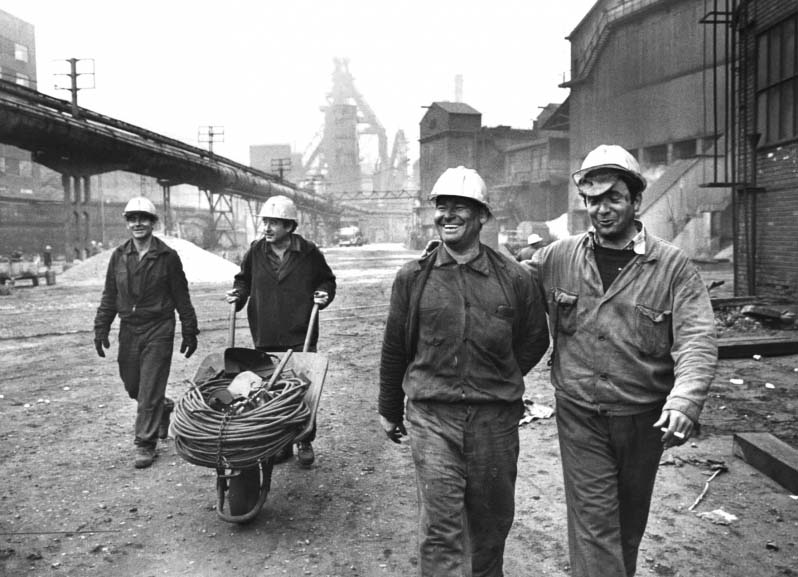

In 1960, at the peak of its operation, 17,000 workers worked there. In this area it eventually had 4 large production centres; the three described when it was created and a fourth devoted to the production of hot rolled metal which opened in 1966 on the plain of Ansio, located in the interior valley of Barakaldo.

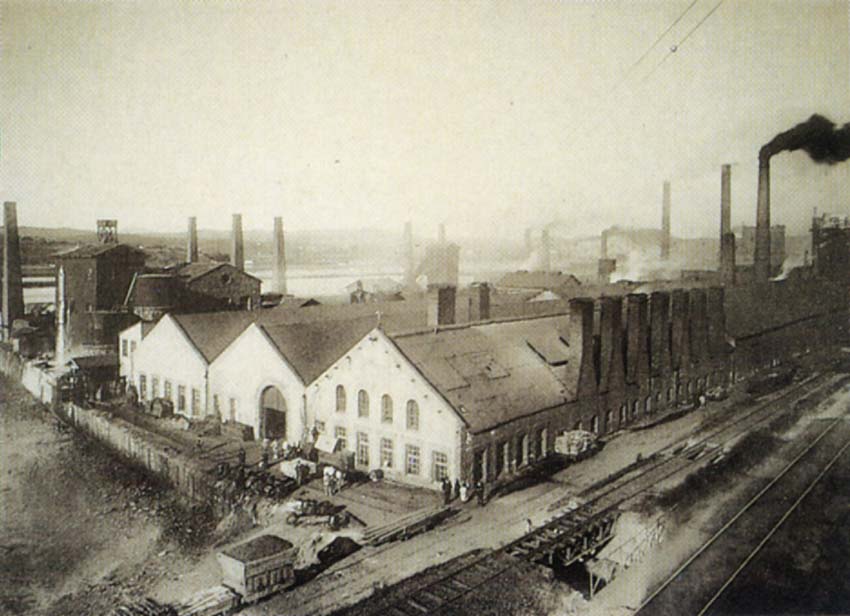

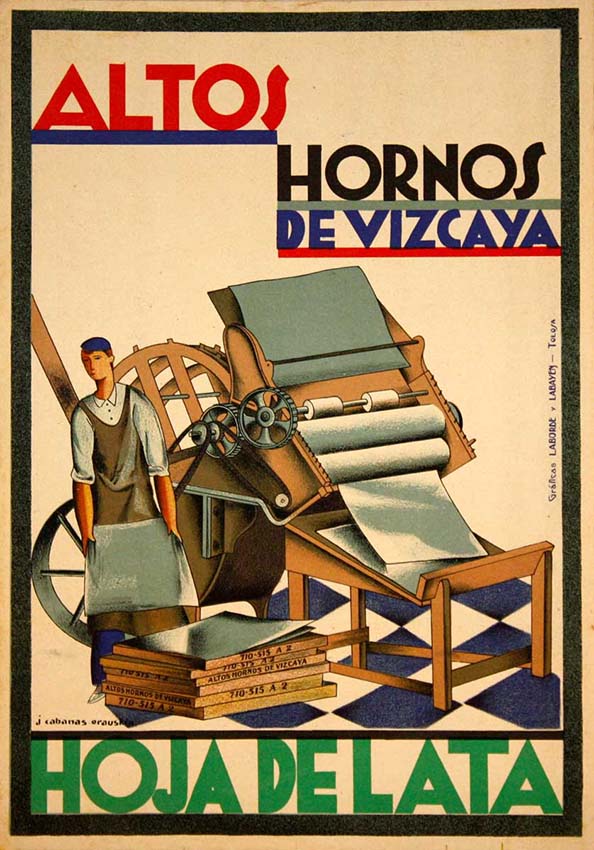

It was a fully-equipped steel mill that turned the iron ore into semi-finished steel products.

More photos of AHV:

PRODUCTION SYSTEM OF A FULLY-EQUIPPED STEELMILL*

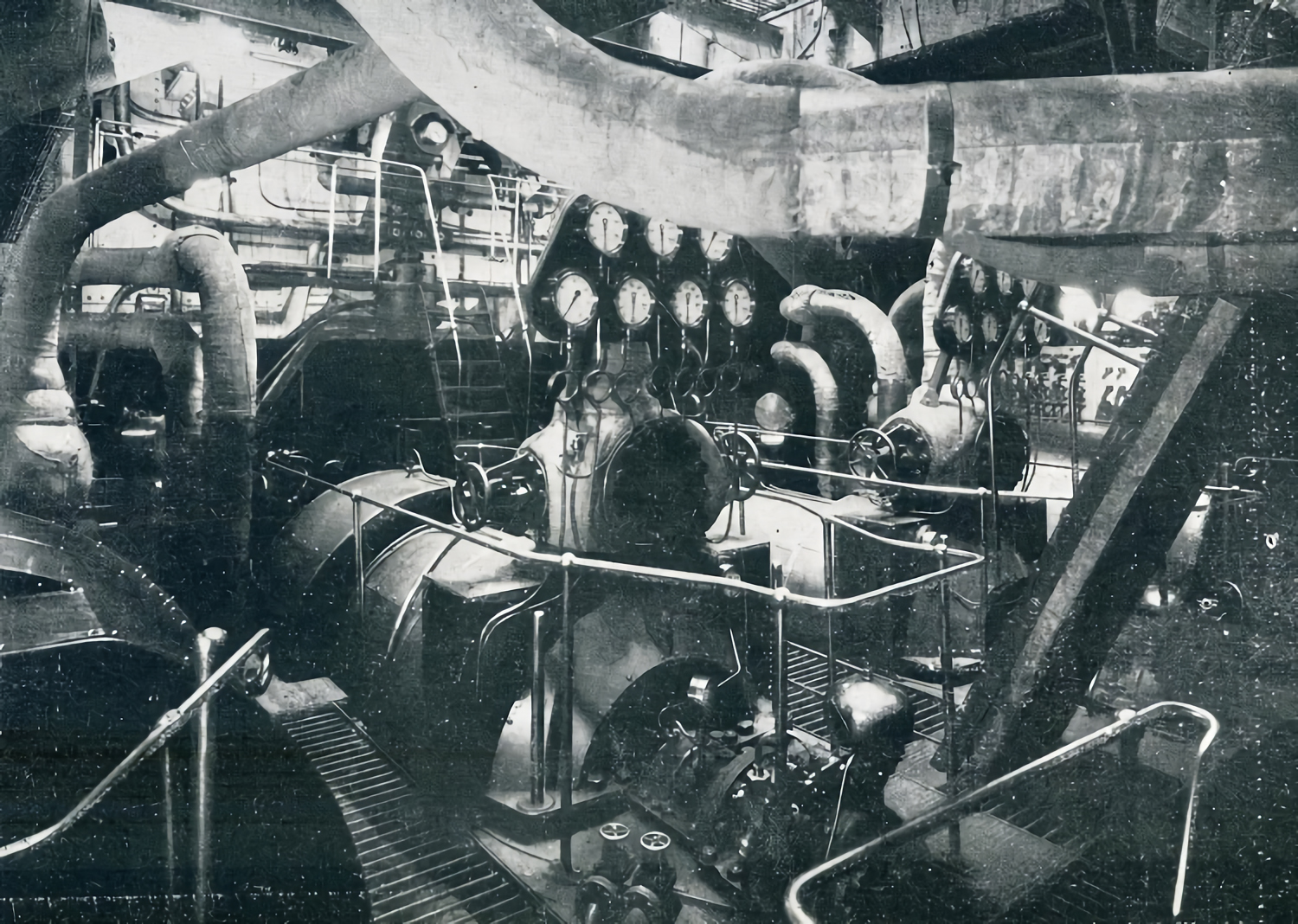

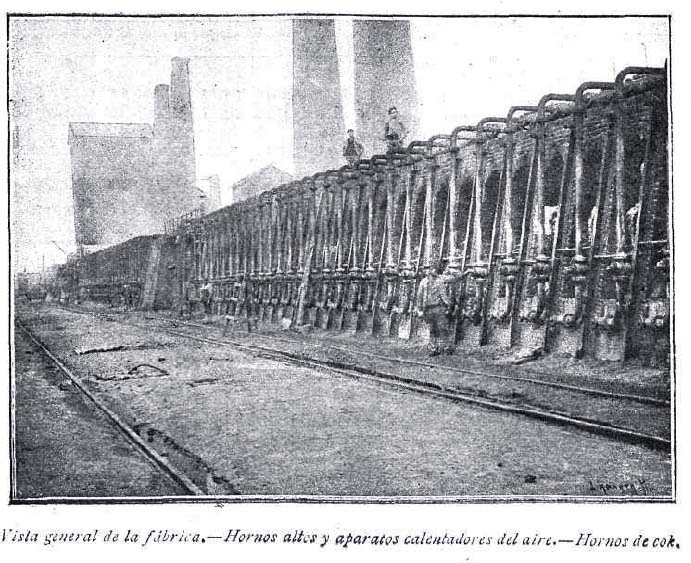

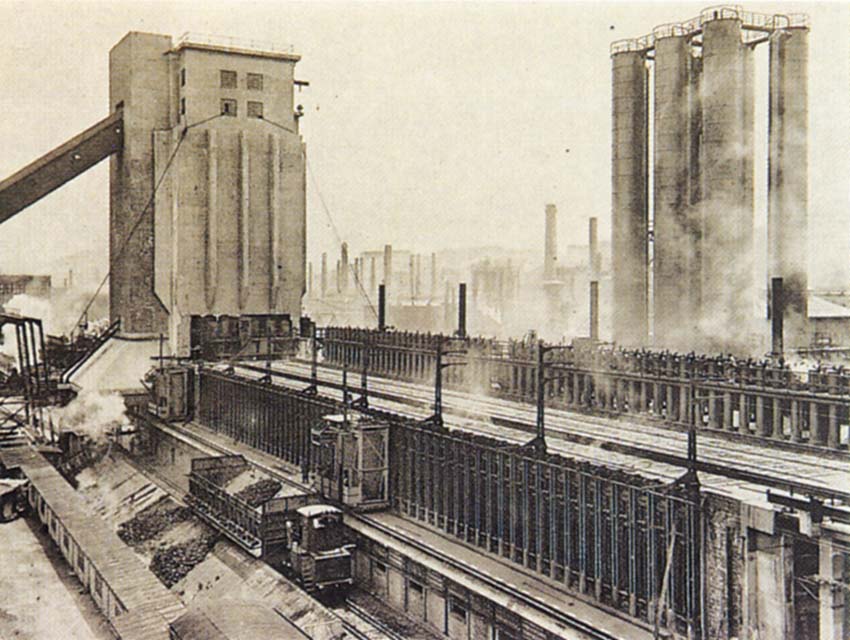

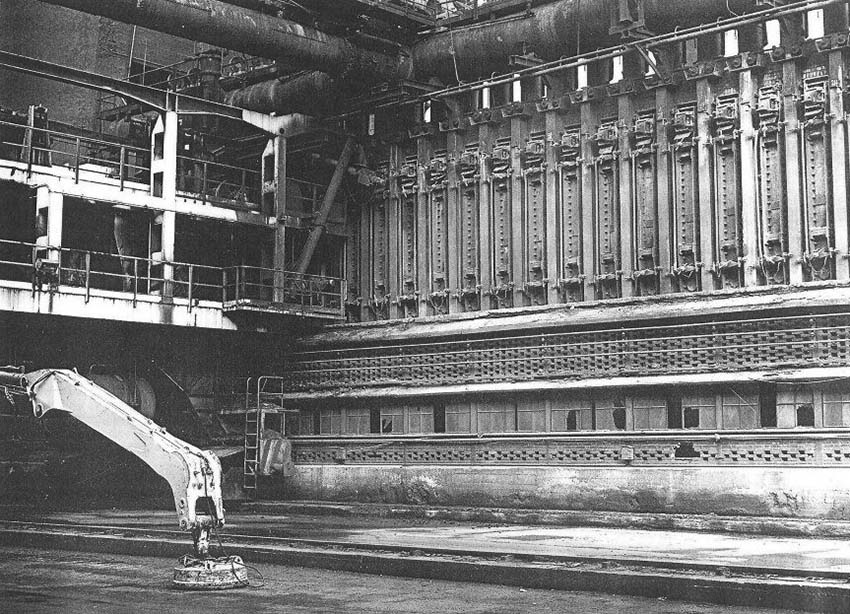

From the beginning, it had enough coke ovens to be self-sufficient in coke. Numerous types of coal were piled up in silos and from there they were fed through hoppers onto conveyor belts carrying the coal to be ground up; there, after removing the ashes, the coal was classified according to its quality and origin. Then it passed to the cooling towers, located above the coke ovens.

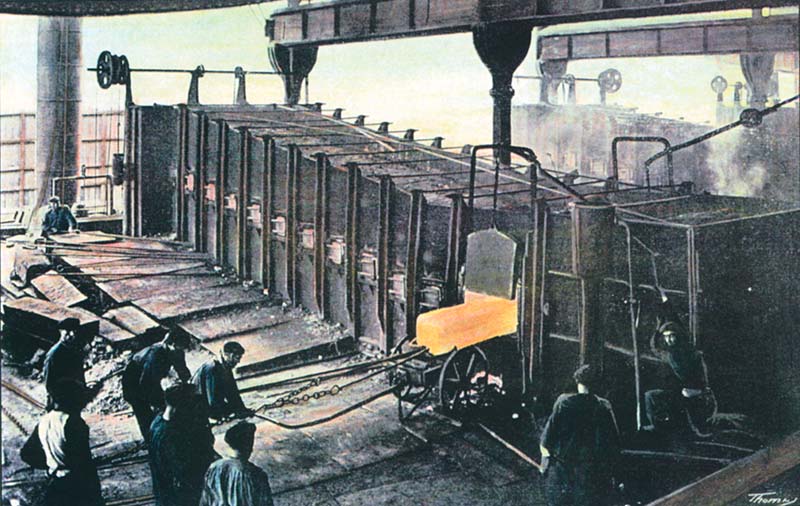

The coal was loaded into machines that fed the coke ovens.

The ovens were lined up so as to not lose heat as a result of irradiation. Each oven was heated with gas from a small adjoining room and one burning session was carried out after another, nearly half of the load. The volatile elements released in the process were used as chemical by-products.

After finishing the coking process, the coke was withdrawn from the retort oven and it was cooled rapidly on the surface; this was done with a cooling tower. The coke was then cut and sieved and depending on its granulometry it was sent to the blast furnace or the different sections of the factory.

For the production of ammonium sulphate there were two sets of tanks to distil ammonia solution. There, the acid was shaken and passed through electric heaters until the sulphate crystals solidified.

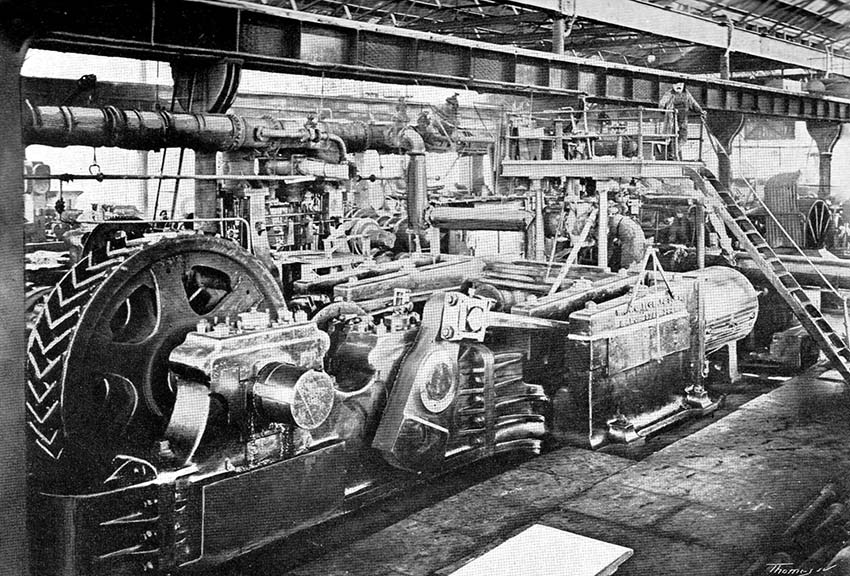

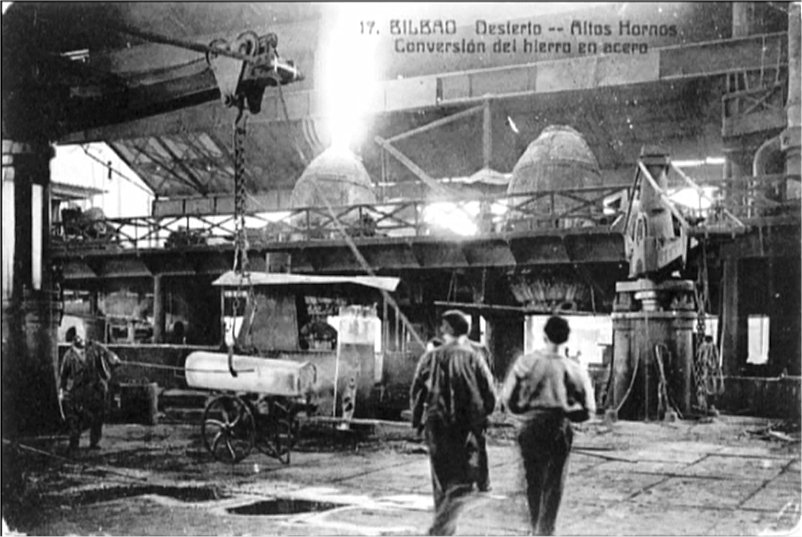

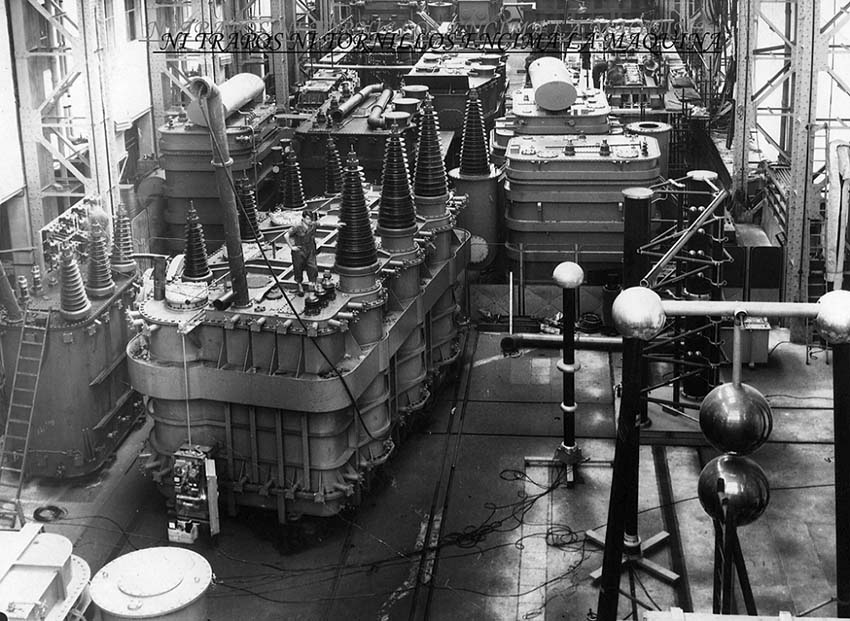

Once the cast iron had been made, the next step was to turn it into steel and for that transformer furnaces were used. Starting with the emerging ingots, all kinds of rolled products were made in the rolling mills.

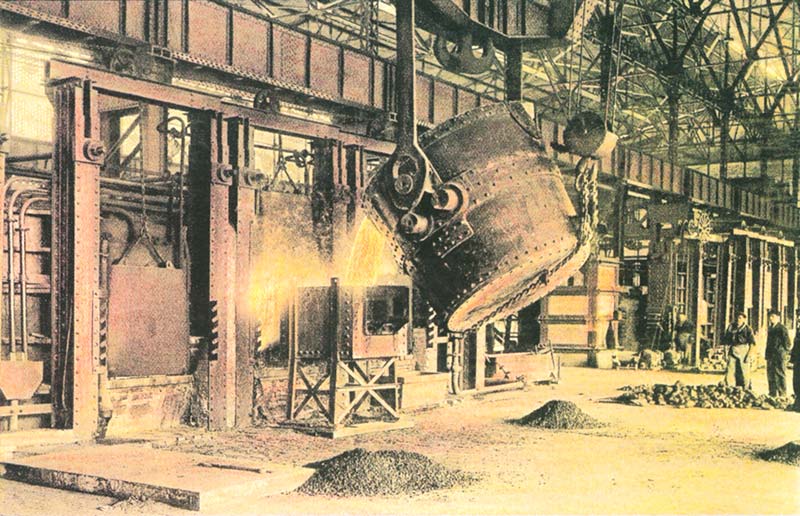

The process in this part was as follows: the steel was poured into a ladle and was transported by a crane over a series of ingot moulds. At the bottom a valve was opened and a stream of steel poured out and filled the moulds. When the liquid steel solidified it became an ingot, which was the first solid appearance of the steel.

Later it was separated from the moulds using cranes equipped with pincers. The ingots were piled up in vertical heat-resistant barrels in which they remained at high temperatures until they were used.

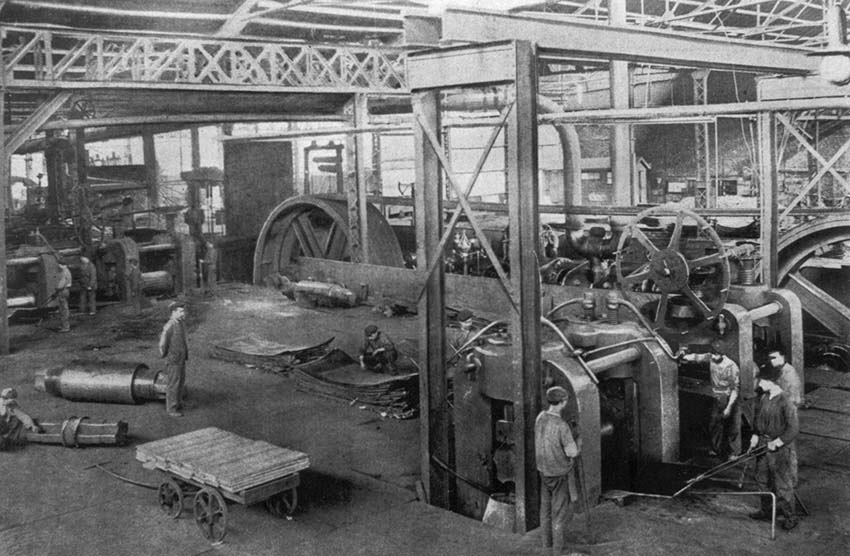

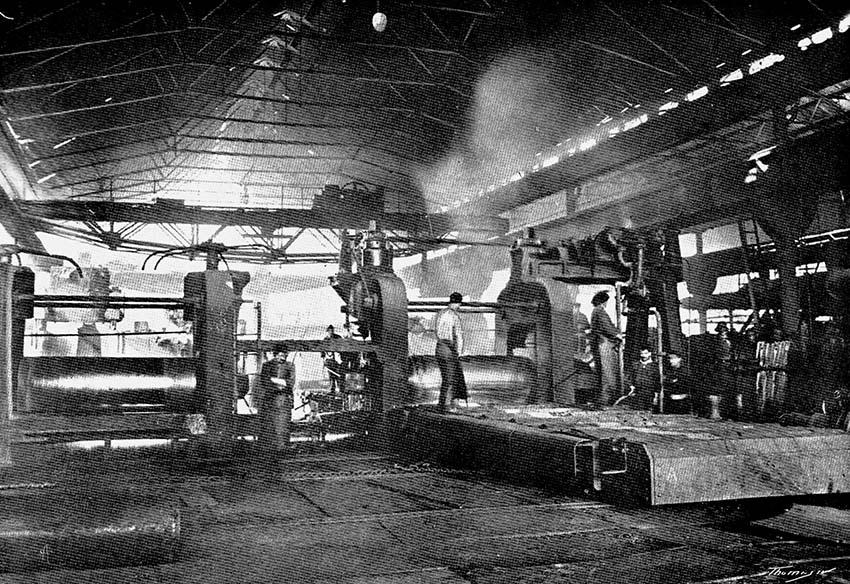

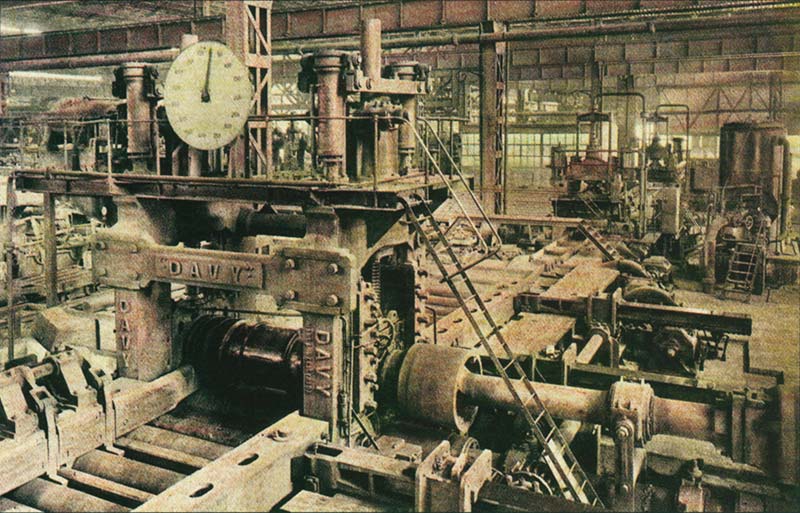

Now in the rolling process, the hot ingots passed through powerful rotating cylinders which narrowed and stretched the section of the ingot under pressure.

In another part of the steelworks, in the structural mills, the bloom (a square plate of steel) was rolled for both heavy construction (rails, bridges, structures for buildings and ships) and for commercial purposes.

To manage this, they had roughing mills with two cylinders that rolled counterclockwise around the ingot: as the surface had grooves, the ingot passed through the mills several times, once for each groove until it was gradually reduced in thickness.

After rolling, the blooms were cut into particular lengths, depending on the purpose that they were intended for, to move them to the rolling mill and give them the desired shape.

*Texts: www.hiru.com

In the mid 80s, the continuous casting process was introduced. Thus, a new steelwork concept was born.

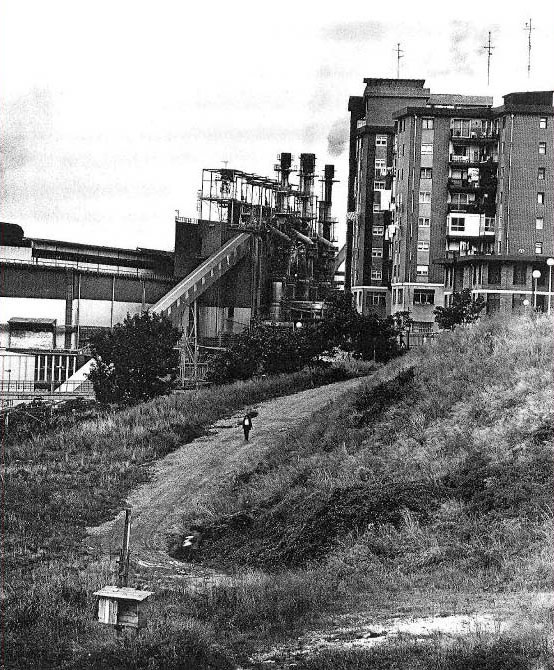

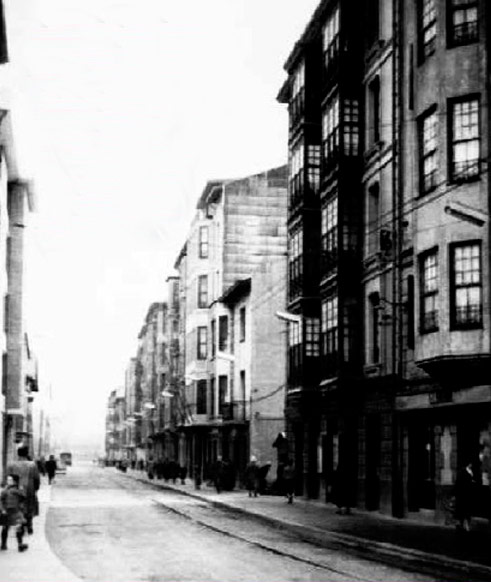

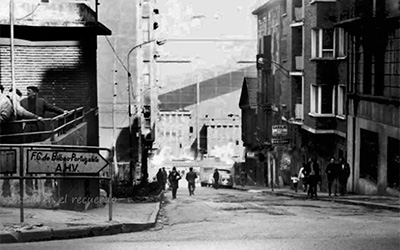

Walking along Rivas street and Txabarri street, we can imagine the enormous, complex installations of this company in what is now ArcelorMittal. Its profound interaction with the surrounding municipalities (especially intense in this town) can be seen perfectly in this street. Txabarri was the main road of Sestao, where its most emblematic houses were, which, ironically, suffered the greatest pollution from being in the vicinity of the factory.

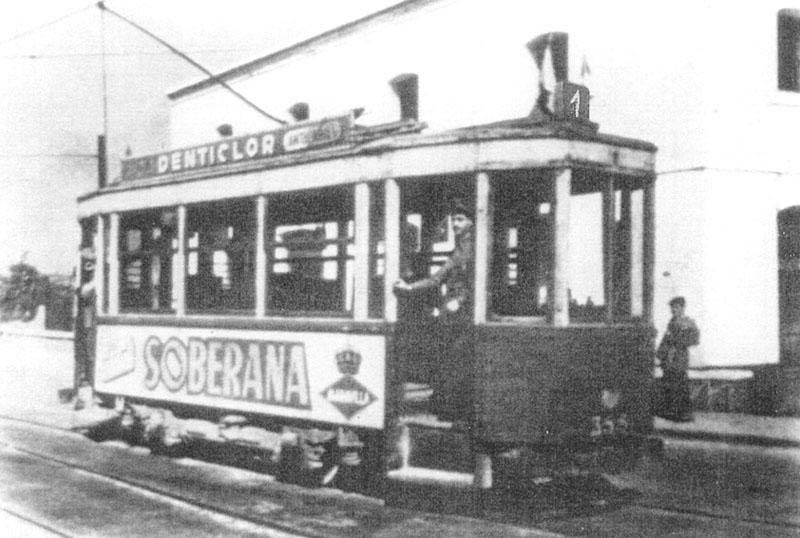

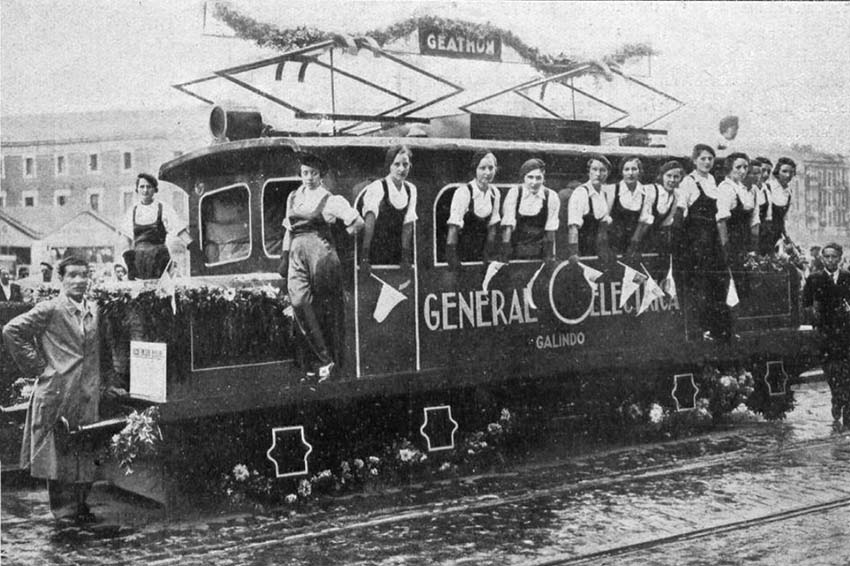

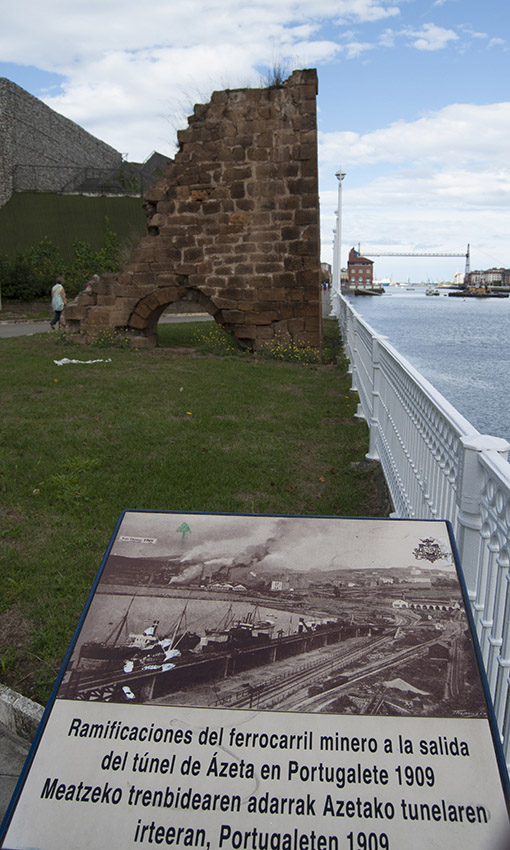

Here the first horse-drawn "blood" tram ran between Bilbao and Santurtzi, opened in 1882, and an electric tram 14 years later. In between, 1888 saw the opening of the railway between Bilbao and Portugalete, which still runs along the bottom of this valley.

The symbiosis between AHV and Sestao was such that people often confused them

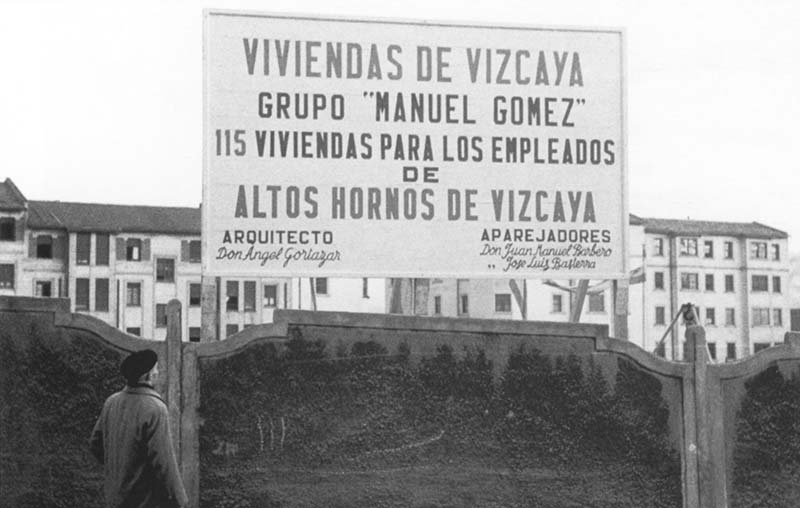

The great company not only occupied most of the surface of this whole area but it also became a property promoter for groups of houses until 1965; it created schools, consumer cooperatives, hospitals and leisure centres. In short, a whole infrastructure that generally saturated the urban areas of Barakaldo and Sestao.

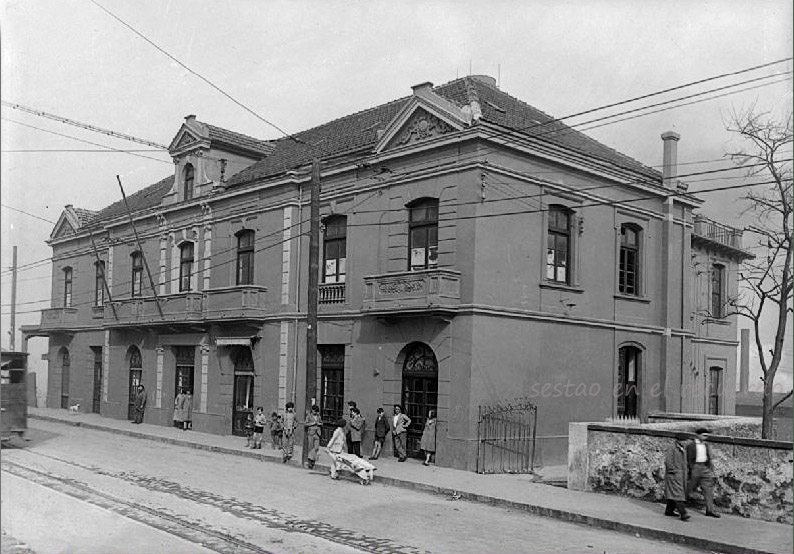

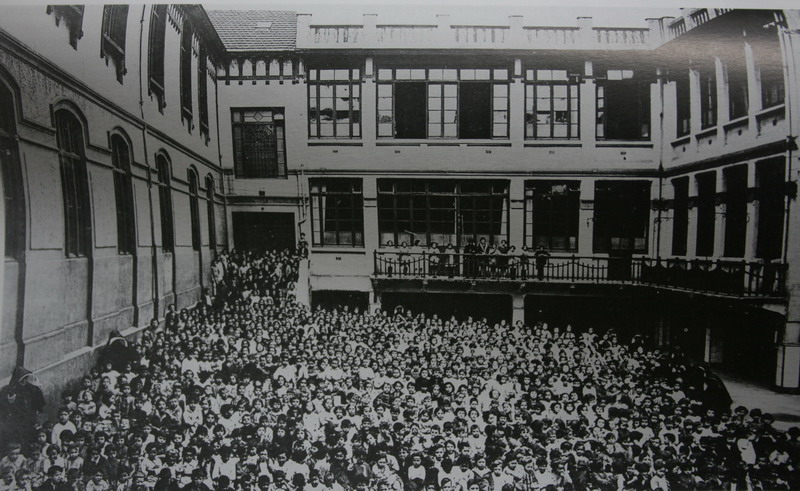

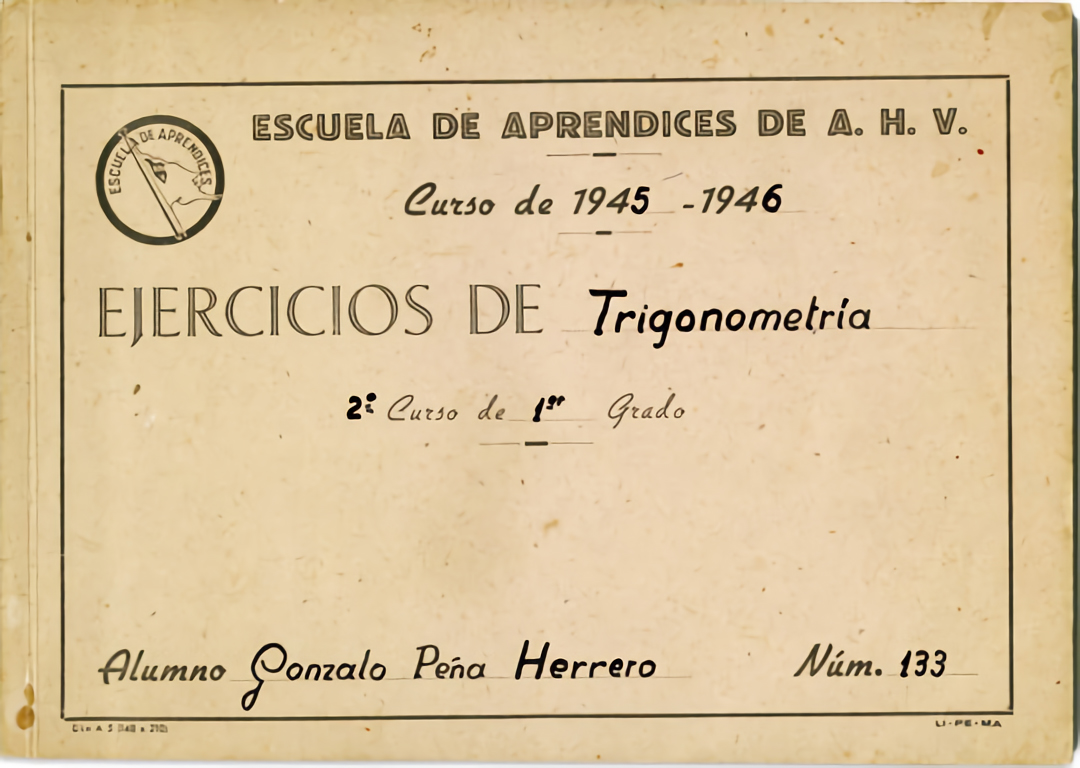

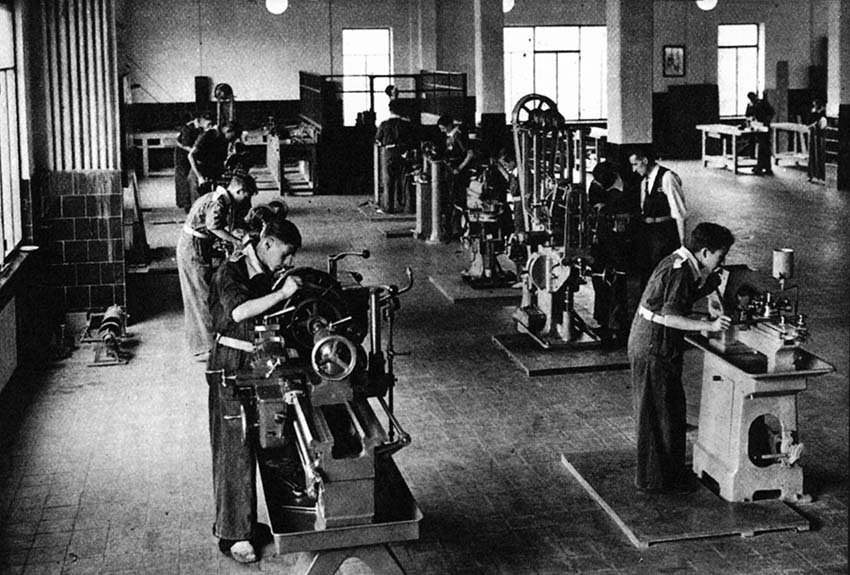

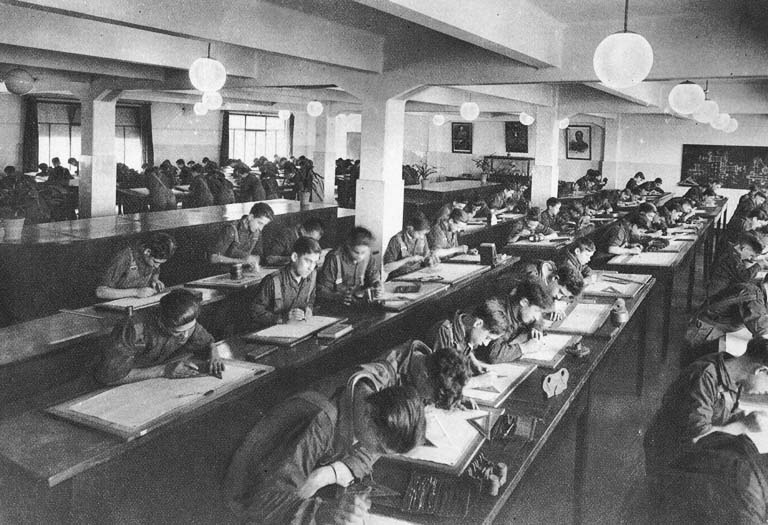

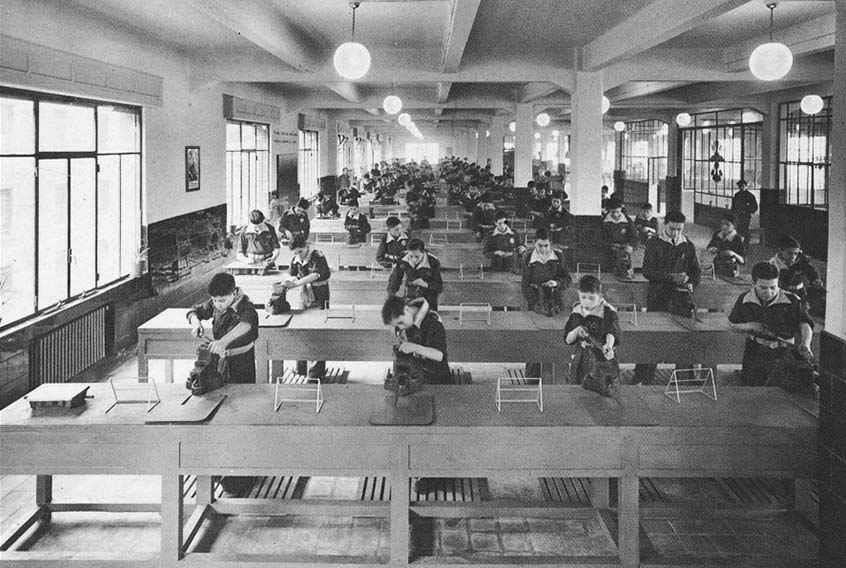

Part of this legacy can be observed in the walk through Sestao. In Txabarri street we pass the old first aid post (8) and 200 m further on, the old School of Apprentices (9) with the company logo on the bars over its windows.

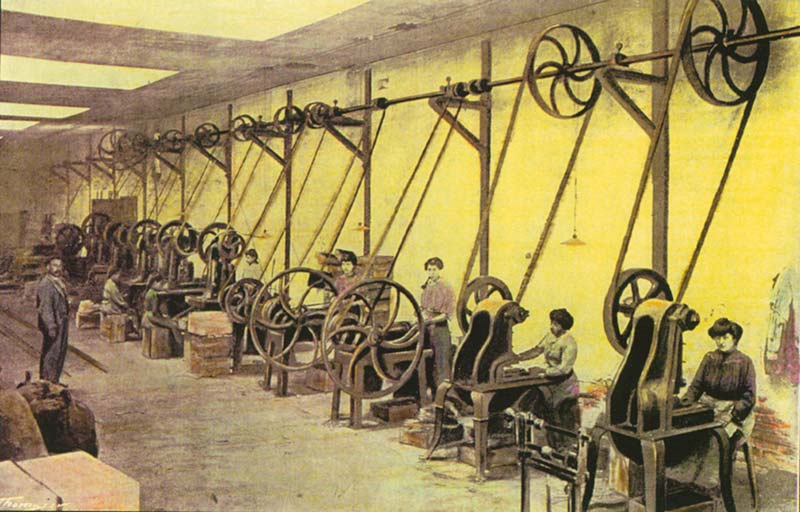

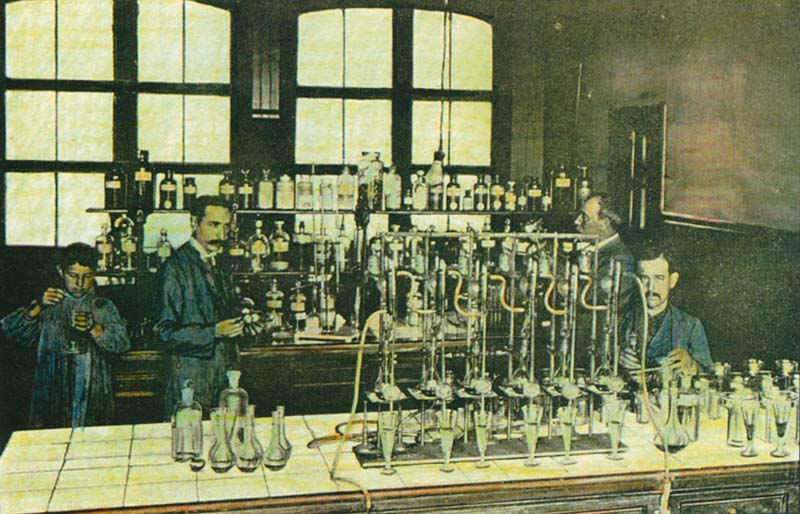

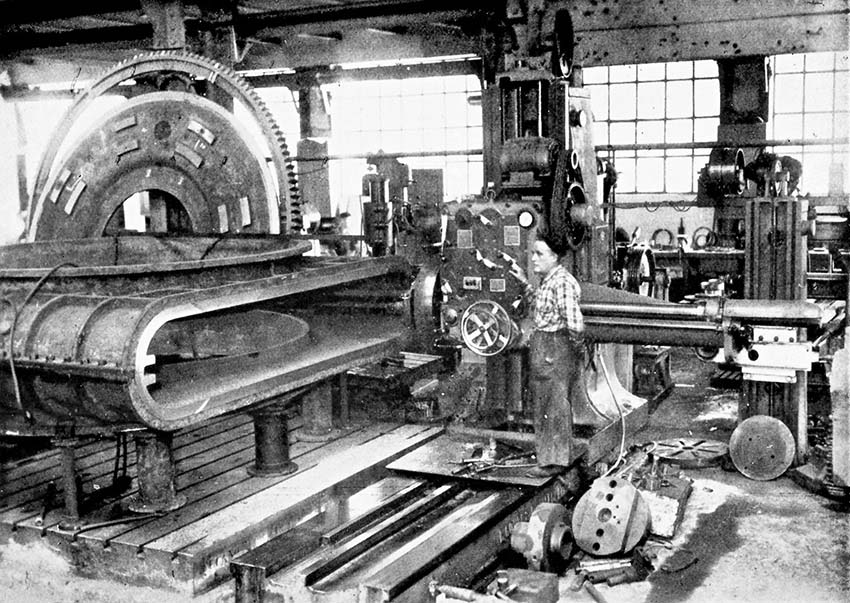

As in other large companies, this school combined studies with intensive in-house practice to train generations of qualified operators to exactly fit the needs of each company. They could be considered the forerunner of today's vocational training.

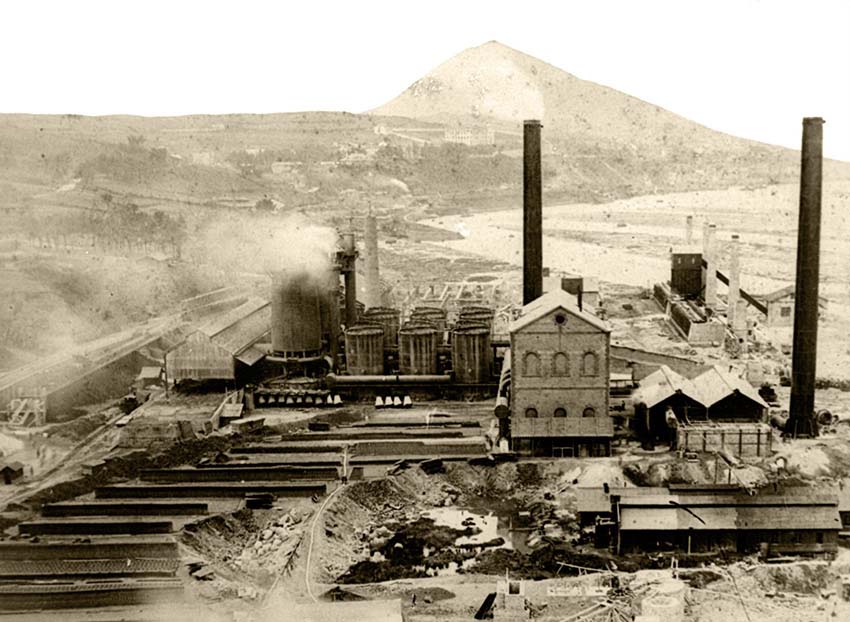

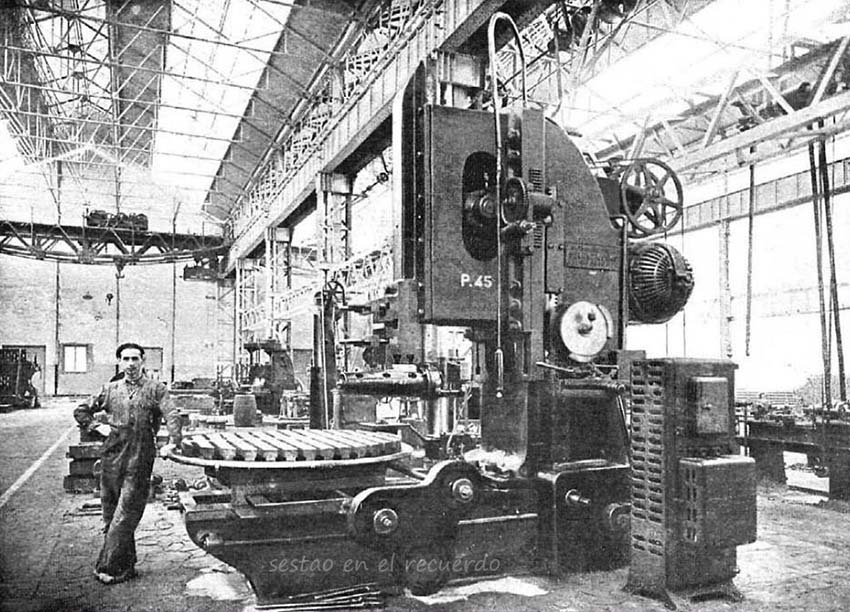

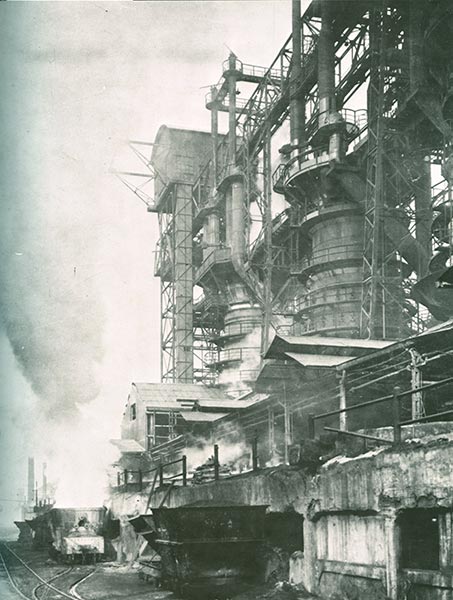

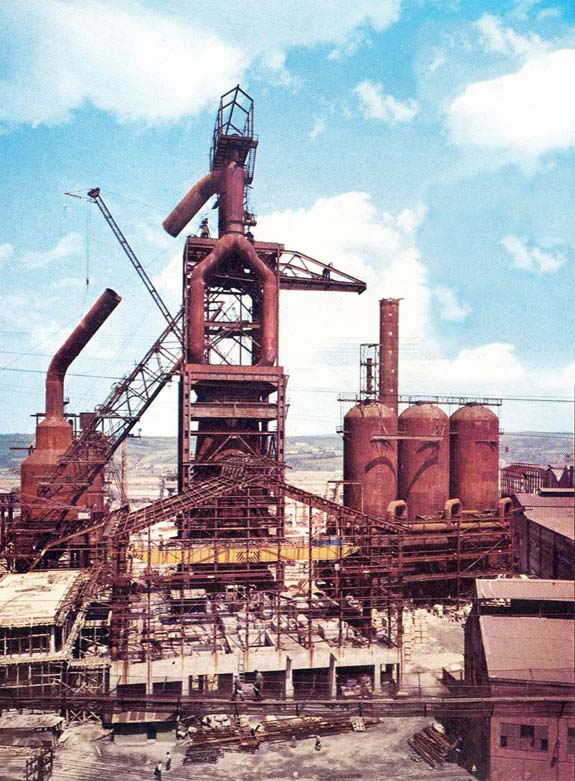

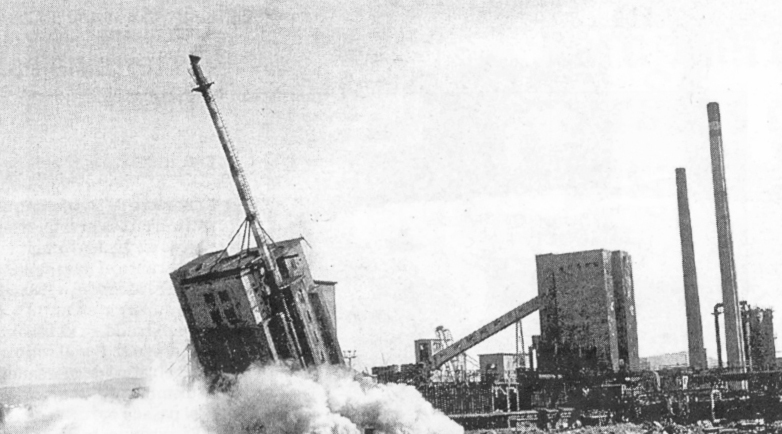

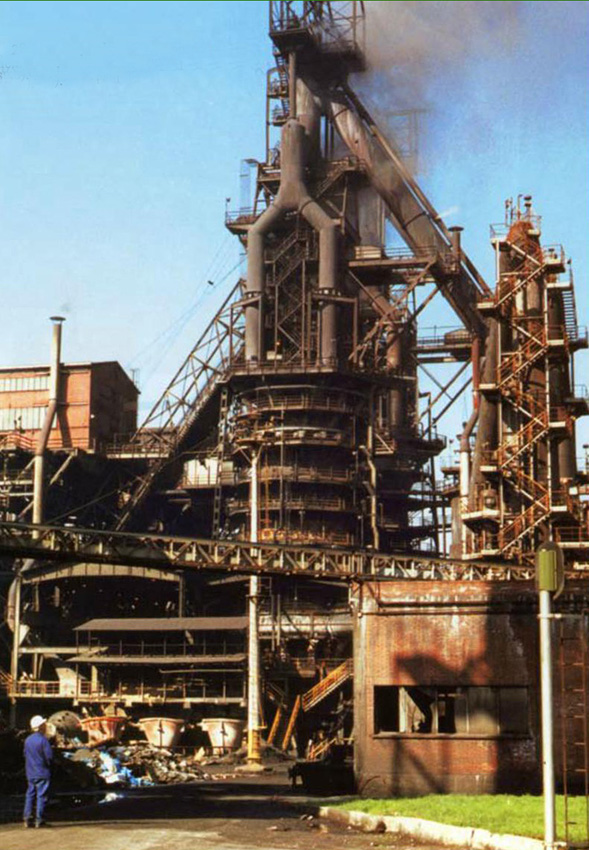

After this building, Blast Furnace No. 1 (Spanish) of 1959 rises majestically (10), the only one left of the 3 that were here, and whose restoration is designed to make it an interpretation centre for the steel industry.

The furnaces were vertical constructions. They were made of a vat covered with welded plate, a shell lined with refractory material.

The total height of the furnace is 80 m and its diameter is 18 m. The main technical features of this construction are its support on a circular beam, the crucible of 6.5 m in diameter, 25 m interior height with a useable interior volume of 757 m3, and the Wurth double bell-mouth inlet ducts for better distribution of internal loads and for preventing gas leaks.

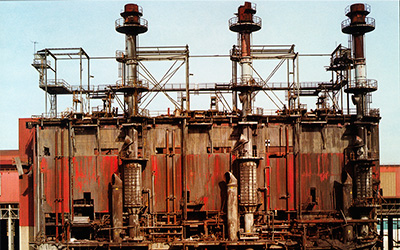

The oven has a series of auxiliary elements necessary for its operation, of which you can still see the three ovens with their chimneys, the flue gas ducts with dust separators, the cable railway for loading the furnace and the casting hall.

The 31-m-high Didier furnaces were forced air intake furnaces, each with 21,247 m2 of heating surface. The gas produced by the furnace was taken away by the outlet tubes, arranged in pairs, which flowed out to a collector and led the gas to a dry filter, reusing part of it to heat the furnaces. For transporting loads of ore, additives and coke, a wagon or skip was used, which was moved by a winch up a slope from a pit in the ground to the feed point at the top of the blast furnace.

In the casting hall where the slag and pig iron were collected, channels or gullies were used to pour them into ladles for casting; also, there was a pneumatic drill and an electric gun, which were used for opening and closing the tap hole.

THE CENTRE OF THE TOWN

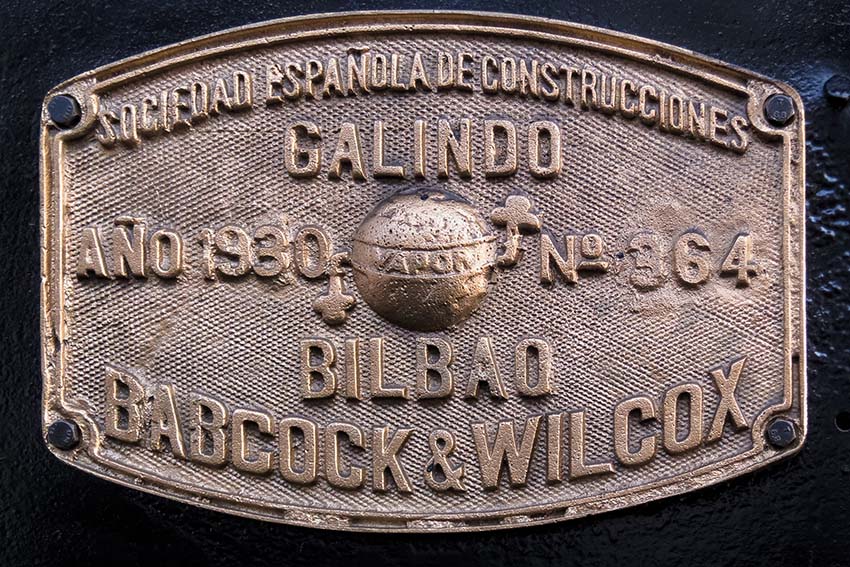

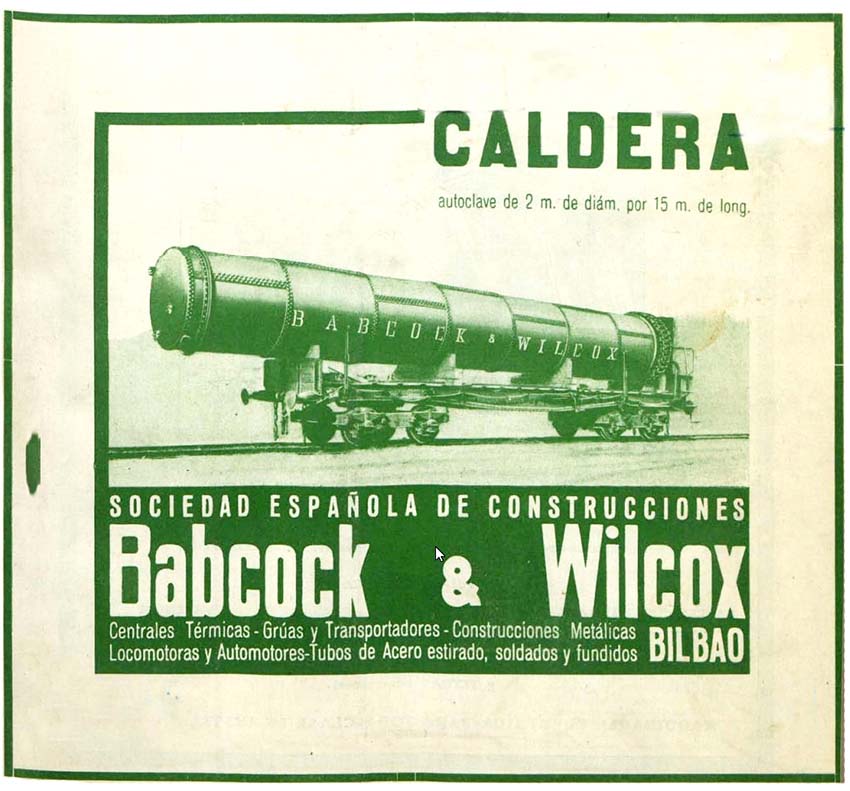

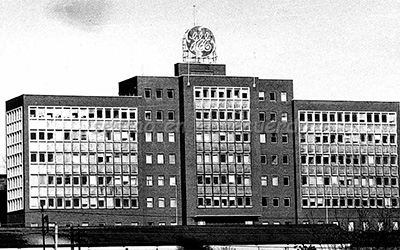

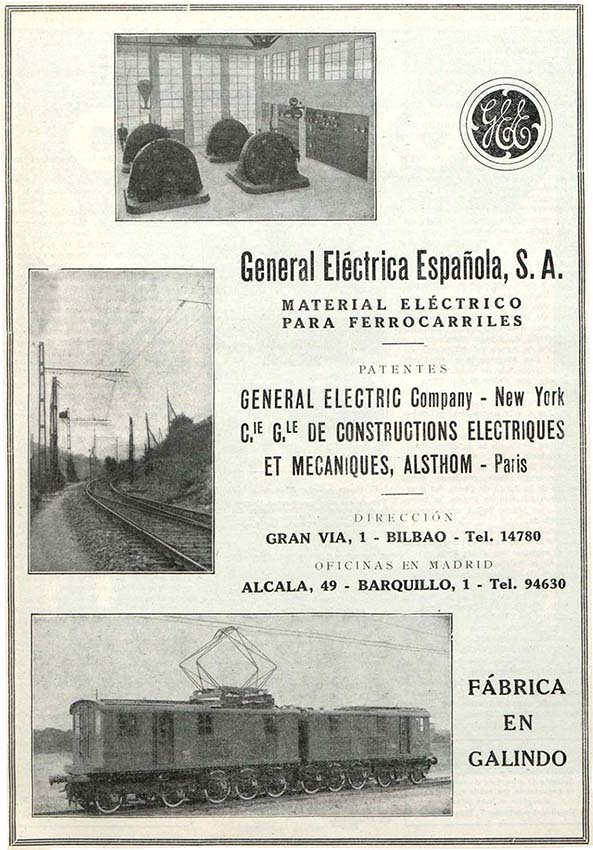

Sestao concentrates its population on the two sides of the hill that separates the river Nervión from the inland valley of the river Galindo where two other large companies were located: Babcock&Wilcox which produced capital goods, and General Eléctrica which made energy equipment and whose original halls are now partially occupied by the multinational ABB.

To cope with the steep slopes, you can make use of the mechanical ramps in La Iberia street connecting Txabarri street to the top of the hill. Once at the top, the first thing you see is what is now the music school (11) painted green and burgundy. Its original function, until 1987, was as the old schoolhouse.

It is a work of 1912 designed by Santos Zunzunegui, the other great local architect of the left bank along with Ismael Gorostiza. Curiously, on the corner of La Iberia street you can see a notice board where the deaths that have occurred in the town are announced, a striking custom of the area.

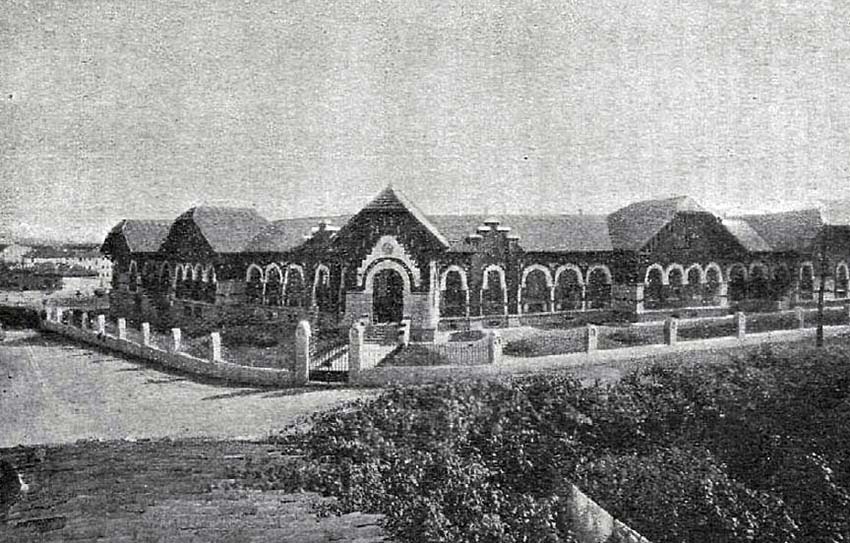

Just across the street (the Gran Vía or high street of the town), is a square with the building in which the first consumer cooperative (12) was reinstalled in the Basque Country.

Created by the steelworkers of La Vizcaya S.A. in 1887, this building, also designed by Santos Zunzunegui, was built when the cooperative moved to the upper area of the municipality in the 1920s. It is interesting to note the concrete reproduction of rivets that mimic a metallic style.

Back at the Gran Vía we go down the second street on the left (Los Baños street) to see various different types of houses again, still linked to the industrial development of the area and the population explosion that happened as a result.

The second junction is La Unión street (13) which is named after a group of terraced houses that run down from this corner of the street. This was another work by Santos Zunzunegui, built, as shown on its ceramic plaque, between 1923 and 1925.

Near the bottom is the "corrala" corridored house known as "La Galana" (14). It is a restored building defined by the fact that the doors of all the flats led out onto a communal corridor where, in its time, the toilets were located in one corner. It was a model of house which was halfway between the previous huts and later types of housing. La Galana is the last evidence left of this type of construction in the last third of the nineteenth century in Bizkaia.

Before continuing this route along the river, we recommend that you go back to the Gran Via and walk 200 m to the left (up the small hill) to see 2 other groups of cheap houses on either side of the street. La Protectora and La Humanitaria (15) will be the last groups of "cheap houses" we see on our walk; both groups have the characteristic English style of the area in the 1920s and, as already mentioned, were a milestone in the quality of life of its inhabitants, under the guidance of humanist architecture.

The route requires us to walk down to the level of the river. We can do it by going down La Iberia street to the bottom or simply going down between any of the streets to see, in all its intensity, the jumbled urban planning that led Sestao to be considered in the 1960s and 1970s one of the points of highest urban density in Europe.

You go down La Iberia street or by the viaduct next to the Blast Furnace down to the quay of La Benedicta (16), going round the most recent part of the Compact Steelworks.

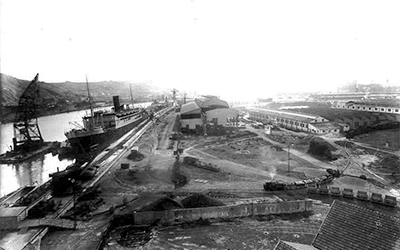

This is as far as AHV extended towards the sea: mineral loaders, freight and passenger railways, cargo ships, tugboats, barges (barge ships of up to 400 tons to transport slag or coal), eternally leaden grey skies, the furnace mouths glistening in the sky and extreme acoustic, water and air pollution...

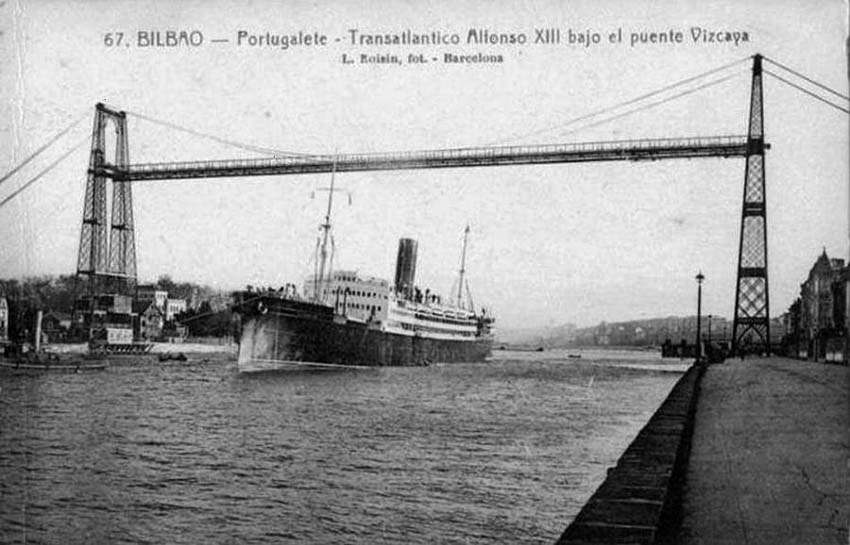

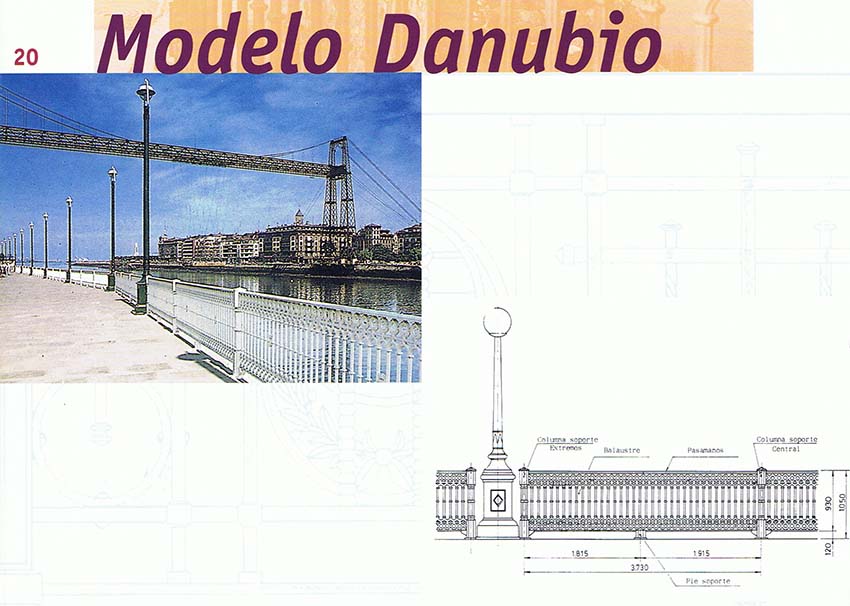

It was a local vision of hell that remained for almost a century and employed thousands of people in an intensive occupation that will never be seen again. An industrial conglomerate that occupied the banks of the river and, as in the case of Bilbao and Barakaldo, made access for the local people to the river difficult. Today, some of these factories have been converted into a convenient, view-filled pedestrian path that joins Sestao and Portugalete, and extends to the next town of Santurtzi. From here you can see the great icon of the area: the Bizkaia Bridge, the first industrial work in operation recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2006.

new naval fleet

new naval fleet