Step 3_ PORTUGALETE. FUSION OF BOTH SIDES OF THE RIVER

Route 3 km

Route 3 km

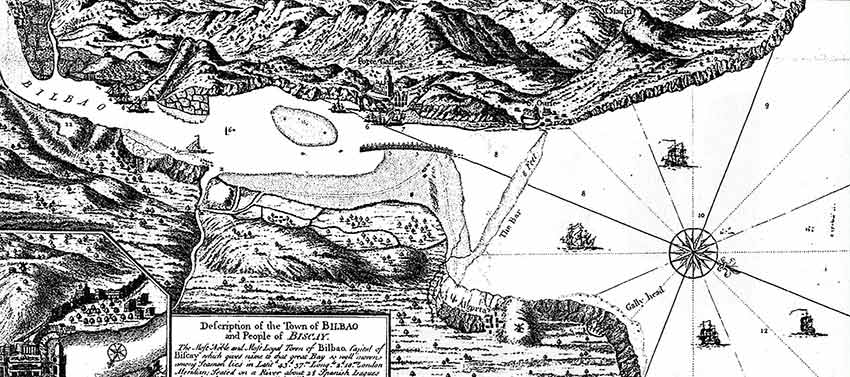

This town was founded in 1322, only 22 years after Bilbao, and it is dominated by the Basílica of Santa María (15th century) which is Gothic with Renaissance influences, and the tower of the Salazar family (14th century), which are both in the same square at the top of the old town.

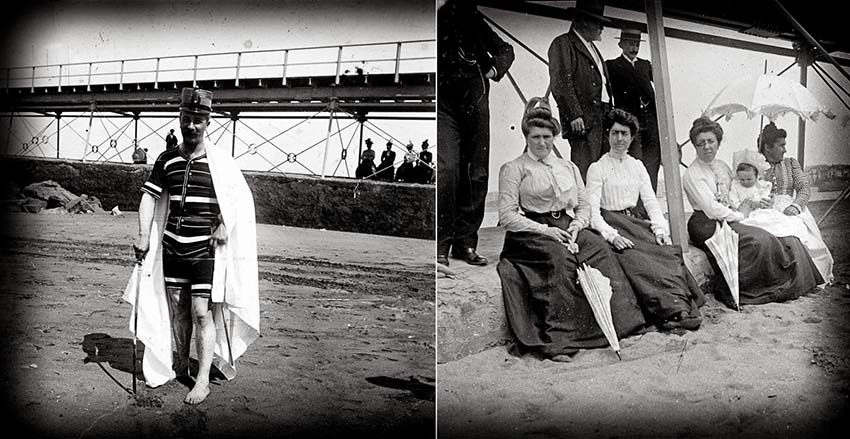

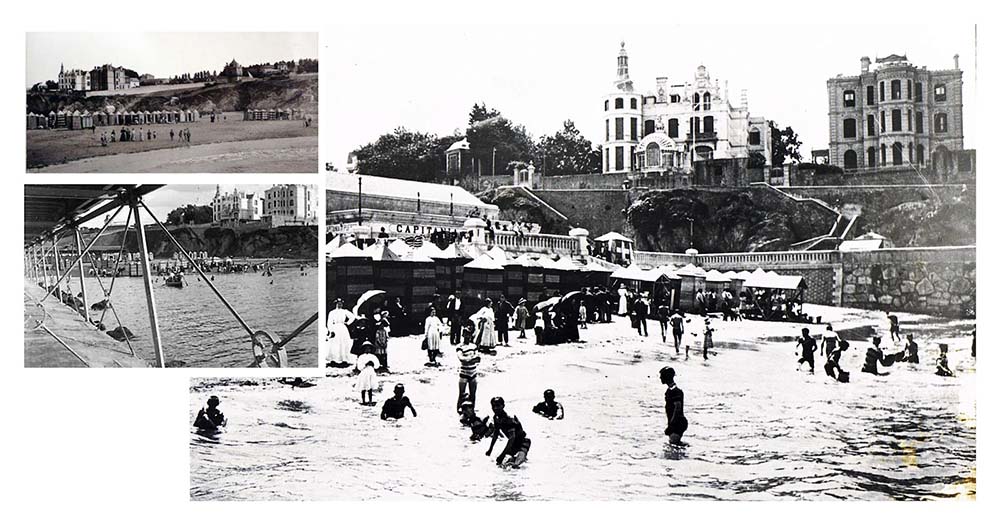

These were two centuries in which the town underwent remarkable development, but it went into decline when Bilbao started to monopolise the activity on the river. In the twentieth century, Portugalete merges the concept of spa town (typical of the opposite bank) at its lowest level down by the river, with high residential density at its highest point (similar to that of the manufacturing towns previously visited).

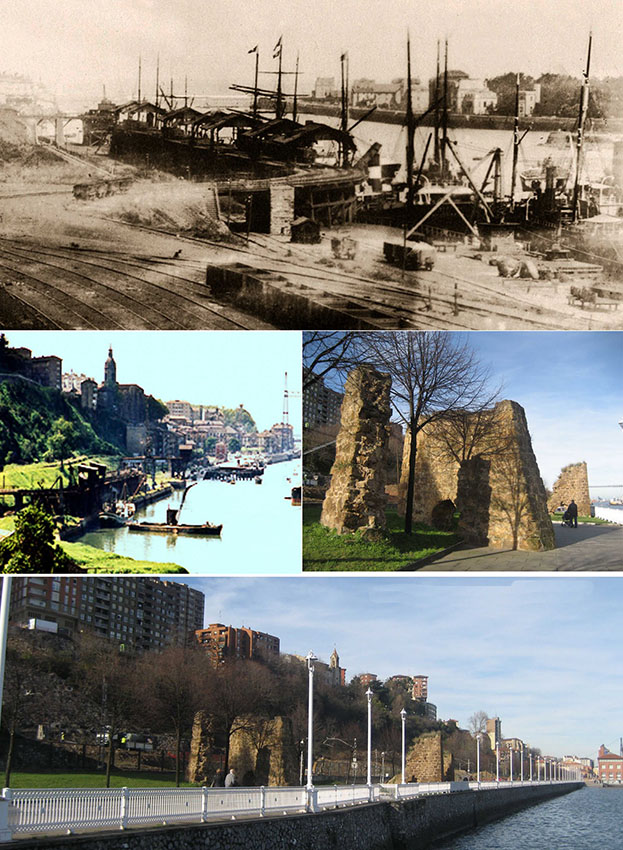

On the way to the transporter bridge, we will see the scant remains of the stone loaders of the Galdames mining railway and, a little further on, in what used to be the building for the port authorities, the Rialia Industrial Museum (Spanish), dedicated to collections and memories of the activity of AHV.

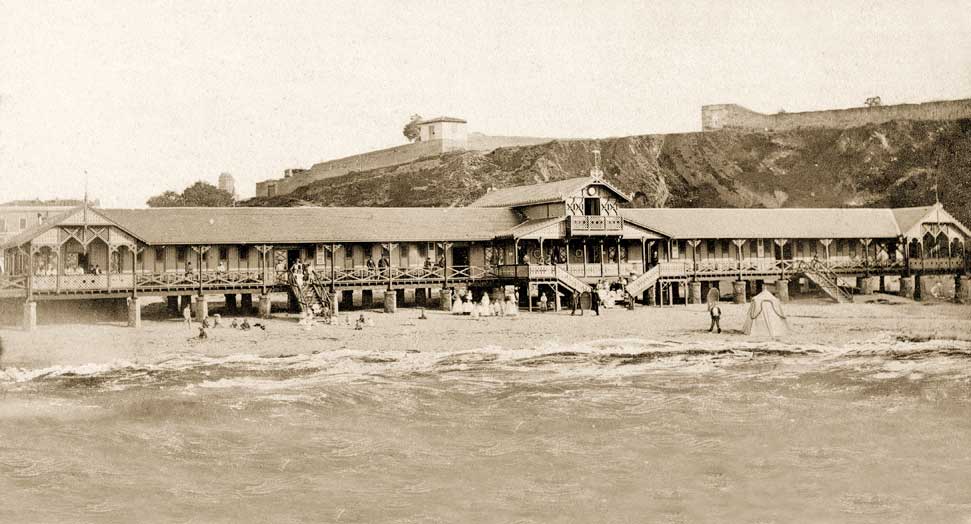

From the era of industrialisation, Portugalete has two listed monuments. One, the famous bridge and the other, the Iron Pier, which solved navigability problems that the river had had for centuries and that became the great exit point for the products extracted or manufactured upriver.

Once you enter the old quarter, you will see a building strikingly painted in yellow and blue. It was the old train terminus La Canilla (17) designed by Pablo Alzola in 1888 as the terminus station of the Bilbao-Portugalete railway line before the train line was extended to Santurtzi in 1926. It currently houses the town’s tourist office.

Just 50 metres ahead on the riverside there still exists a system of alternative transport to the transporter bridge: the motorboats that also connect both sides.

In the 1970s there were up to 7 crossing points on the river for ferries between Bilbao and Santurtzi. Today there is only this one, and the one at the quay in Desierto, in Barakaldo.

Above is the Plaza del Ayuntamiento, or Town Hall Square. In the background you can see the Bustamante House (18) designed in 1910 by the Cantabrian architect Leonardo Rucabado with clear influences of Catalan Modernism.

From this square, from the corner of the Gran Hotel, continue the walk along the river, where you can see a variety of large houses and mansions.

THE GREAT ICON OF INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY: DREAM OR BUSINESS?*

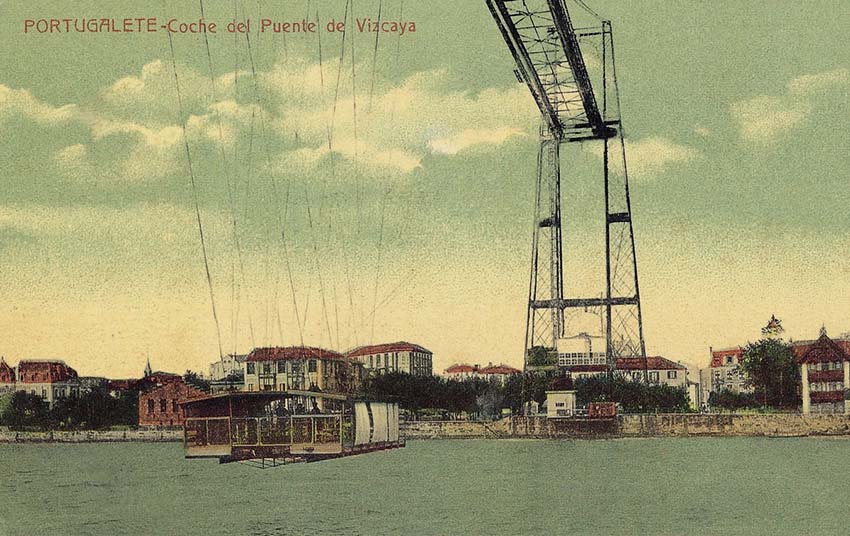

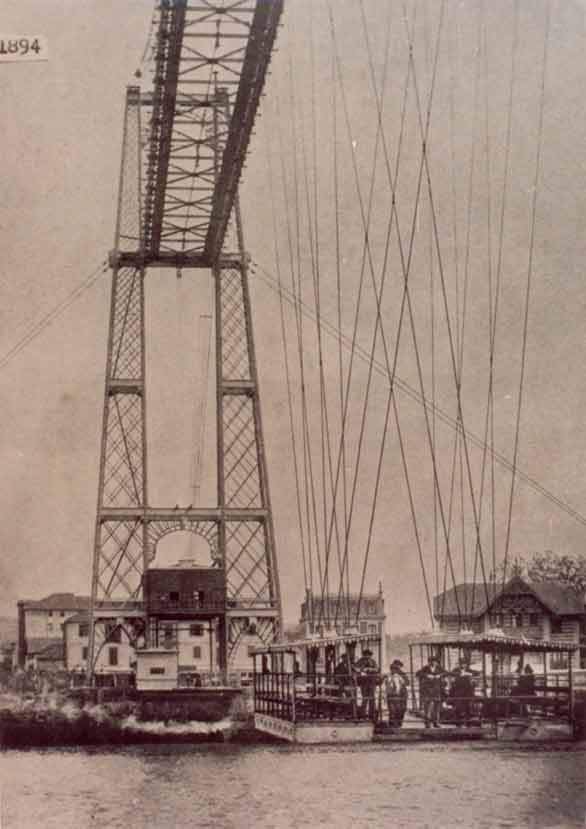

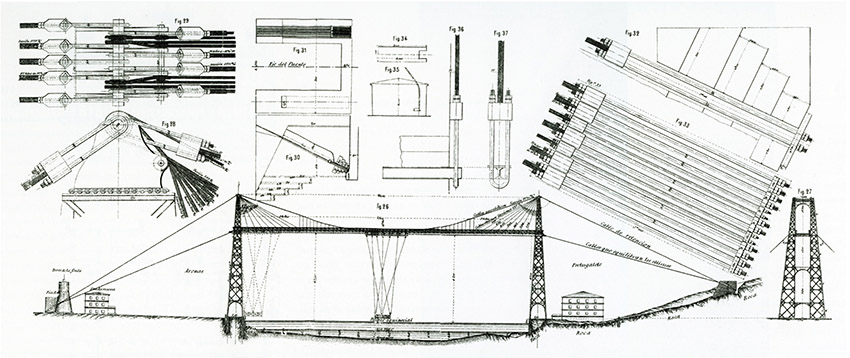

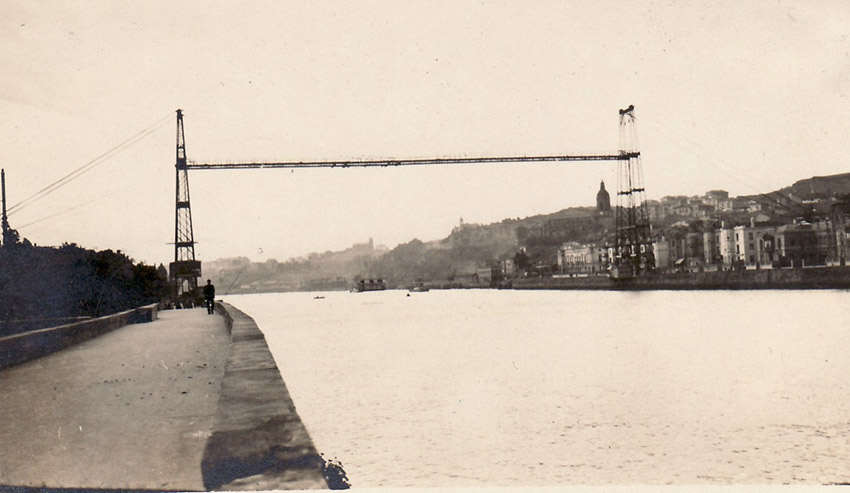

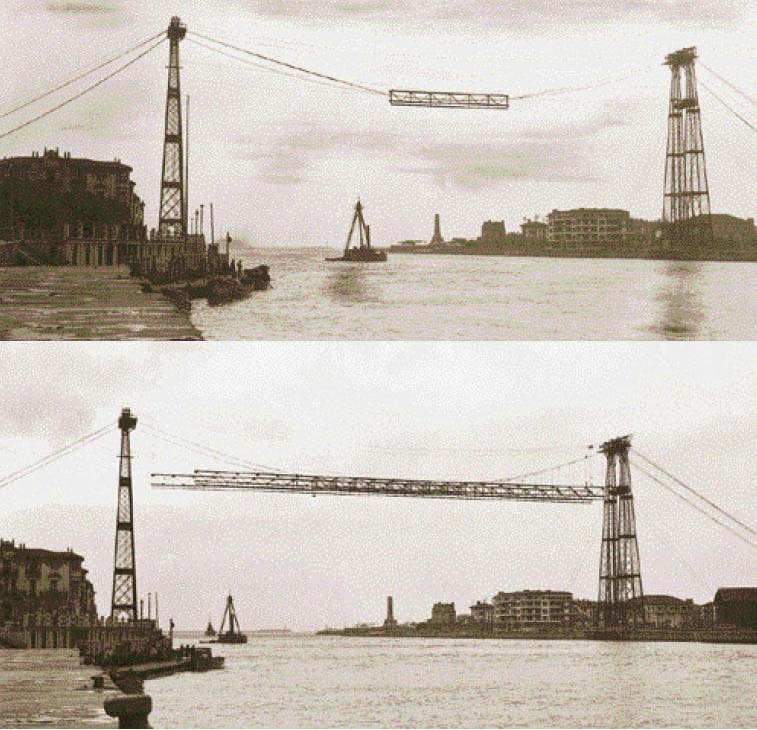

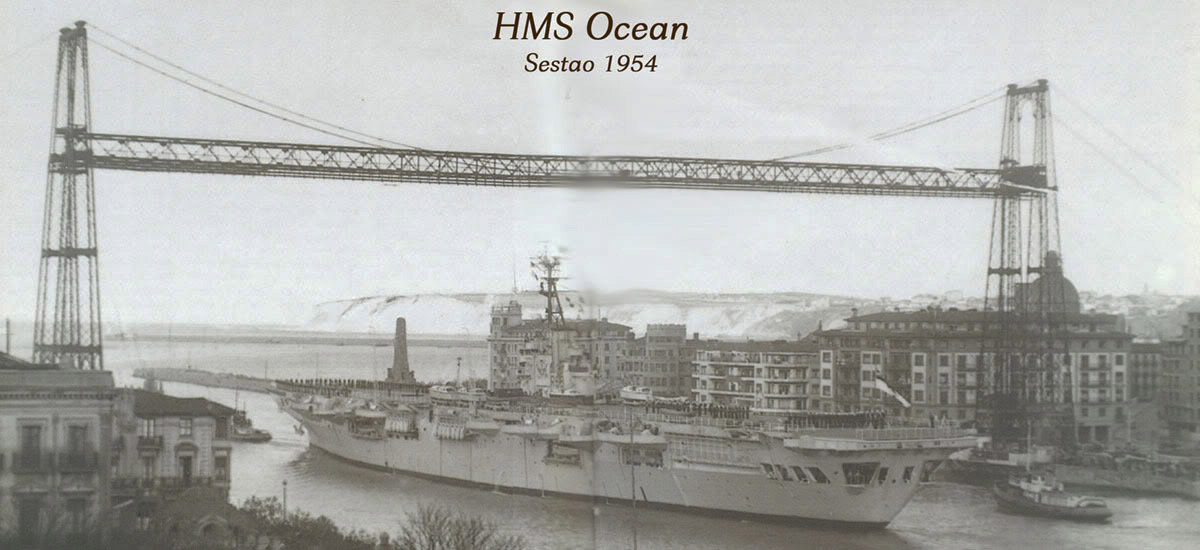

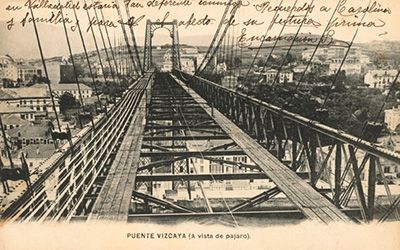

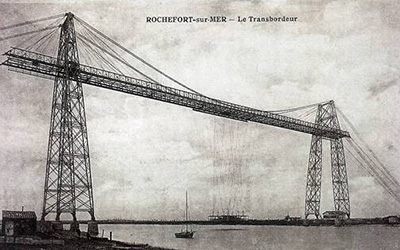

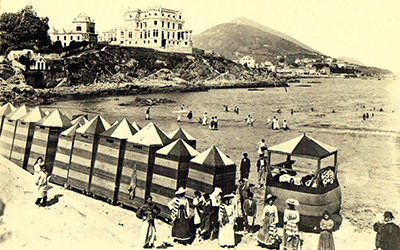

The Bizkaia Bridge (19) embodies both. It is a transporter toll bridge, conceived, designed and built by the private sector between 1887 and 1893, linking the two banks of the Nervión River and was the first of its type in the world. Its construction was due to the need to link the existing spa resorts on both sides of the river, for the industrial bourgeoisie and tourists of the late nineteenth century.

In 1887 Alberto de Palacio met the contractor Ferdinand Arnodin. The Frenchman was attracted by Palacio’s project and provided techniques for suspension bridges with cables that he had developed in his earlier projects. Thus, the "Vizcaya Bridge" in terms of Transporter was Palacio’s invention, and in terms of Suspension was Arnodin’s. Fortunately it was both at the same time and that's what made it original and new.

As new as the money that financed its construction. At a time when multimillionaire fortunes were being forged at the edge of the river, none of the mining magnates nor the richest ship owners, none of the bankers nor any of the wealthy patrons of the biggest steelmaking centre in the peninsula risked getting involved in this project to connect the two sides of the river with an iron bridge.

The absolute novelty of the project made the great names in the financial pantheon of Bilbao look on it sceptically. Neither did they see a lucrative business in the transport of passengers over short distances. It would be twelve modest businessmen linked to trade and light industry who would embark on the adventure. Among them, one stands out as the true entrepreneur of the work: Santos López de Letona. The role of López de Letona is worth emphasizing, because it embodies an archetype of Basque economic tradition: the figure of the "indiano", the rich emigrant who made his money in America.

Returning to Europe with a healthy fortune, he decided to invest in the project of the Transporter Bridge, which goes to show his forward thinking and confidence in industrial progress.

In addition to being the one who brought the most capital to the venture, he imposed his serene, rigorous spirit and managed to dispel the disputes that arose between Palace, Arnodin and partners of the Company. And there were many, because the construction of the "Vizcaya Bridge" proved slow, complex and not without controversy between the forces involved. It did not follow the initial project plan in the technical conditions, the budget or the deadlines.

Suffice to say that although work began amid great optimism on August 4th, 1890, in 1891 they progressed with agonizing slowness, due to legal problems, the reluctance of the builder and the mistrust of the partners. So much so that there were times when the very existence of the monument hung by a thread. Differences between the technical director (Palacio) and the contractor (Arnodin) began almost immediately. Arnodin acted with an entrepreneurial mentality, while Palacio saw the bridge as the pursuit of a personal dream that it was always possible to improve, with plans that he never took for definitive.

It was inevitable that the inflexible pragmatism of the Frenchman would collide with the boundless youthful imagination of the Basque. The investors did not understand this tense dialogue between the creator and the dealer, and watched the struggle with distrust. Added to this was the anguish of thinking that their savings would vanish if the government did not renew their work permits because of the delays.

The work was so new and the architect's mind so active that the transporter bridge changed and mutated as he went along. He understood that he could exploit the potential of the structure as a leisure resource and make it part of the landscape of the summer amusements of the beaches of El Abra.

Alberto de Palacio's visionary character led him, at that time, to propose cafes and restaurants, elevators and a walkway above

The partners were delighted with the idea, but Arnodin responded with great reluctance; for him the original plan was "a light economic construction". Palacio and Arnodin ploughed ahead together, almost always with many doubts and reproaching each other for the delays; one accusing the other of being slow in manufacturing and the other diagnosing him with an incurable "maladie des changements", or disease of changes. But amid all the problems, the group of men set on the construction of the "Vizcaya Bridge" was held together by the contagious faith of Alberto de Palacio in his project and by a unanimous feeling of being involved in a transcendent work. They were not mistaken.

On July 15th 1893, the last missing piece to complete the gigantic meccano arrived: a "Henri David" water pump made in Orleans. Everything was quickly mounted on a platform above the arches of the first floor of a nearby building and on the 24th the bridge was ready to be tested. The machinery started with a tremble, the gondola started moving, the cables tightened and yet the great metal skeleton remained rigid, without deflections or vibration. The bridge worked. And it still does today. It even offers the possibility of crossing the river along its upper walkway, with its superb views of the river and the river mouth.

It was a model for other similar bridges around the world later. There are numerous panels around it explaining its details, the process of construction or the repair after the Spanish Civil War. It works continuously every day of the year 24 hours a day. Its current colour was inspired by the red hematite iron seam of Somorrostro.

*Texts: www.euskadi.eus

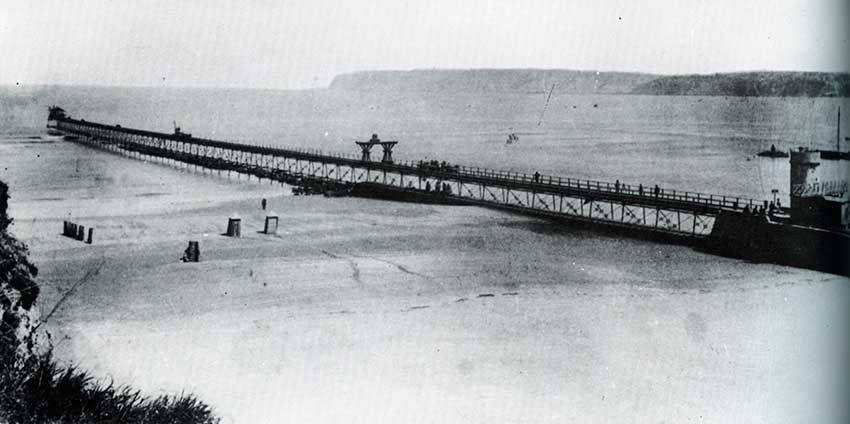

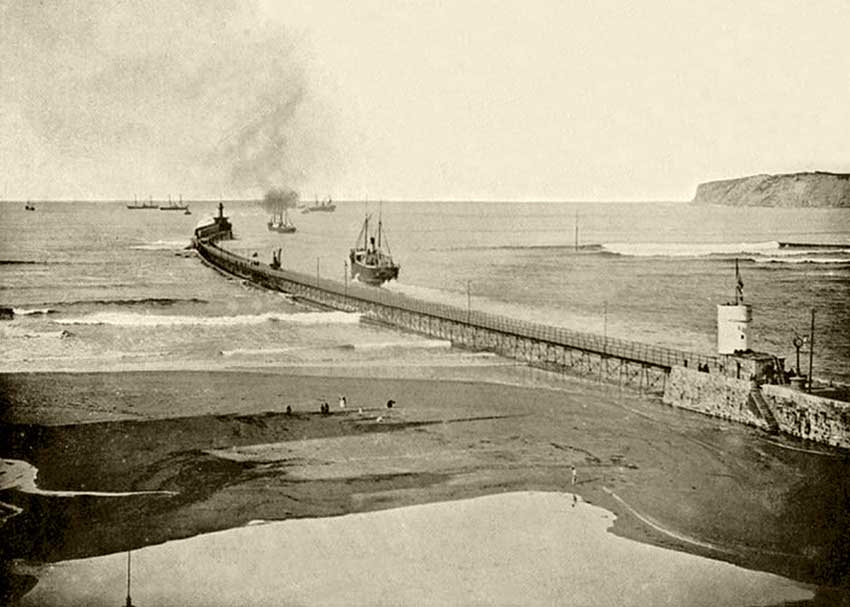

THE IRON PIER: THE CONSTRUCTION THAT DROVE THE DEVELOPMENT OF BIZKAIA

Now, we will just go past it to get to the other great jewel of this trip: the Iron Pier (21). In addition to the imposing bourgeois houses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, on the walk you will see a clock that is actually a tide gauge (20) installed only two years before the opening of the Iron Pier. The substantial form of this structure has to be imagined today. The point of the walk where the pier begins used to be Portugalete beach; in fact, you can see towering beachside houses on the hill now converted into hotels and municipal services.

This beach was connected to the opposite bank by a sand bar that, throughout history, made it very difficult to navigate the river; the dreaded Portugalete sand bar - also known as the school for shipwrecks – made of shifting sands that hindered navigation periodically, sometimes making it impossible at low tide (with depths of only 1 m).

Centuries of dredging and cleaning were not able to clear this important gateway to the river of Bilbao for ships with enough draft for the iron trade, and this explains the profusion of unprotected loaders on the cliffs from outside the current port right round to the neighbouring province of Cantabria.

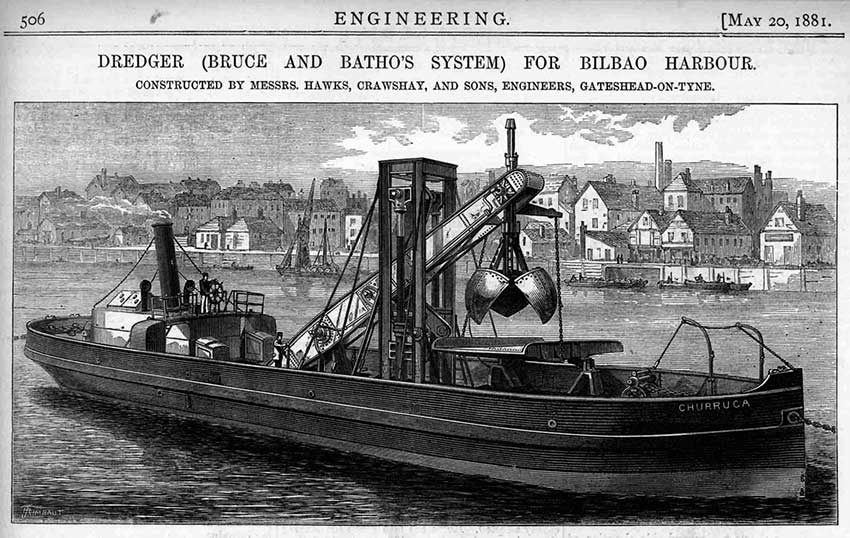

Evaristo de Churruca

The work was finished in 1887 and its construction finally solved the problem of navigability in the port of Bilbao, creating an eighty metre wide step with a depth of 4.58 m at low tide; Churruca would be recognized for his worth in the field of European civil engineering. It is a work that explains exactly how the term genius is the etymological basis of the word engineer.

We retrace our steps back to the Bizkaia Bridge and go over to the opposite shore.